“Wow!

What a book!” So shouted W. M. Krogman in the Chicago Sunday

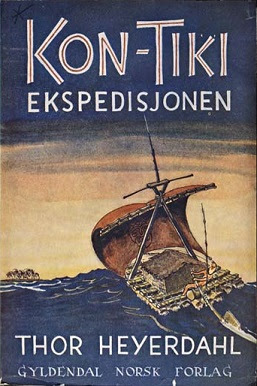

Tribune of Kon-Tiki,

saying the aforementioned exclamation could easily comprise his

entire review. But he went on anyway gushing, "It has spine

chilling, nerve tingling, spirit-lifting adventure on every page and

in every one of its 80 action photographs. It is the fiction of a

Conrad or a Melville brought to reality. It might be added that the

writing is of itself worthy of either pen.”

Krogman

wasn't the only reviewer enthralled by the

story of six Norsemen who sailed 4,300 miles on a balsa-wood raft

from Peru to Polynesia. Heyerdahl's account

won wide critical acclaim upon its publication in 1950 and went on to

bestsellerdom, translations into more than five dozen languages, and

the ultimate stamp of approval:

inspiring an Oscar-nominated movie.

Today

it's considered a classic. But its

fate might have been oblivion

outside Norway (where the first edition sold out in a couple of

weeks) had William Styron's opinion held sway. The young manuscript

reader at McGraw-Hill rejected the book presuming no one would want

to read about six guys on a raft in the South Pacific. Fortunately

Styron's counterpart at Simon & Schuster saw enough merit in

Kon-Tiki

to persuade senior editors there to take the risk, and they gambled.

And, as we know, won big.

I'd

be wondering if sheer luck hadn't been in play in the future

classic's denial by a future Pulitzered novelist were it not for

Styron's admittedly shitty attitude at McGraw-Hill. His “failure

to project an appropriate work-man’s appearance and...slacking on

the job” got

him fired a couple months after being hired, which he fictionalized

in his celebrated novel Sophie’s

Choice

further down the road. Else I’d be tempted to juxtapose the role of

any of the gushing critics with that of the budding literary star,

and guess then

who would do the gush and who the flush—a fantasy that appeals to

my cynical perception that despite its pretensions mainstream

publishing’s all about the sizzle and to hell with the steak.

None

of this mattered to me at the time as I shared Styron’s sense of

Kon-Tiki,

not at all intrigued by the prospect of reading the log of a long,

lonesome sea adventure (I’d thought at the time it involved only

Thor Heyerdahl, whom I assumed had to be more than a little nuts and

probably a mediocre writer at best). It was a disinterest I carried

for decades despite knowing of Styron’s embarrassment and the

book’s ultimate wild success. I carried it right up until a couple

of weeks ago when a friend who’s a regular visitor to Peru and

student of its history and culture recommended Kon-Tiki

in a way that Styron, had he actually read the book, should have

recommended it to the editors at McGraw-Hill.

|

| Heyerdahl |

I am now in agreement with W.

M. Krogman’s enthusiastic “Wow! What a book!” with the

qualification, however, of substituting “story” for “book,”

as I cannot agree with his assessment of the writing as rising to

Melville’s or Conrad’s lyrical heights. Heyerdahl was a

scientist. His writing is accomplished and engaging. But it’s his

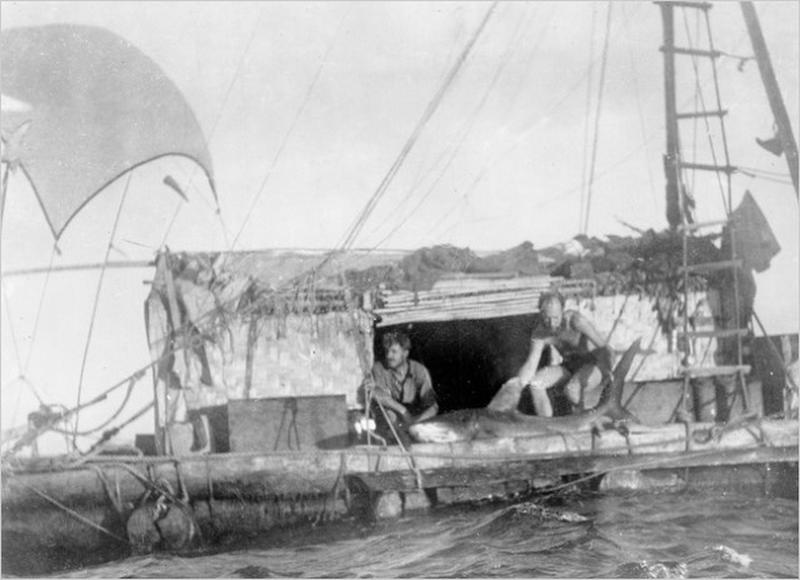

story that matters, that excites and astounds. He gives us in minute

detail such a vivid depiction of six men with no seafaring

experience—Heyerdahl couldn’t even swim—alone on a raft for 101

days at the mercy of the planet’s greatest ocean merely to prove a

theory, that present-day Polynesians had done the very same thing a

millennium earlier, led by Kon-Tiki, their chief, floating on balsa

rafts from Peru into, for them, The Great Unknown. Heyerdahl’s

story begins with his finding evidence of Peruvian culture during

scientific study on a Polynesian island. It continues with his

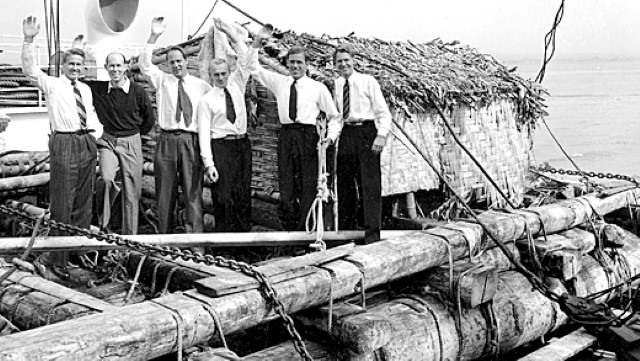

winning support for his dream of recreating the oceanic journey,

gathering his five crew members and building and outfitting his raft

to approximate as closely as possible the same conveyance used by the

earlier Peruvians to flee their country and start a new life in

another world.

In

his foreword to the book’s 35th

anniversary edition,

he

calls the 1947 launch of Kon-Tiki

“the most decisive moment in my life, when I, a sworn landlubber

with a fear of water deeper than to my neck, cut all ties to the land

and steered out into the largest and deepest body of water on earth,

into a strange adventure and an unknown future.”

The

Kon-Tiki’s

bold journey, he said, “proved that a prehistoric voyage from South

America was possible, contrary to the predictions of scientists and

sailors. The South American balsa raft, which scholars had claimed

would sink if it were not regularly dried out ashore, stayed buoyant

as a cork. And Polynesia, held to be inaccessible for a watercraft

from ancient America, proved to be well within the range of

aboriginal voyagers from Peru.”

Here’s

part of an entry to the daily logbook he kept during the crossing:

May

17. Norwegian Independence Day. Heavy sea. Fair wind. I am cook today

and found seven flying fish on deck, one squid on the cabin roof, and

one unknown fish in Torstein’s sleeping bag...

He continues in the book, “If

I turned left, I had an unimpeded view of a vast blue sea with

hissing waves, rolling by close at hand in an endless pursuit of an

ever retreating horizon. If I turned right, I saw the inside of a

shadowy cabin in which a bearded individual was lying on his back

reading Goethe with his bare toes carefully dug into the latticework

in the low bamboo roof of the crazy little cabin that was our common

home...

“Outside

the cabin three other fellows were working in the roasting sun on the

bamboo deck...”

He had no trouble raising his

crew. All five were enthusiastic volunteers when they learned of

Heyerdahl’s quest. Getting financial support was another kettle of

fish. “We could apply for a grant from some institution, but we

could scarcely get one for a disputed theory; after all, that was

just why we were going on the raft expedition. We soon found that

neither press nor private promoters dared to put money into what they

themselves and all the insurance companies regarded as a suicide

voyage; but, if we came back safe and sound, it would be another

matter.”

Help came finally in

Washington, D.C. from the Norwegian military attaché, Col. Otto

Munthe-Kaas. When he learned of their trouble raising funds, an early

enthusiast of Heyerdahl’s proposal, he stepped up to the plate.

“You’re

in a fix, boys,” he said. “Here’s a check

to

begin with. You can return it when you come back from the South Sea

islands.”

I grew up in a town named

after the man I’d learned in school represented the epitome of

heroic adventure, the man who “sailed the ocean blue” in either

the Nina, the Pinta, or the Santa Maria. Later on I added “Lucky

Lindy,” who flew the ocean blue in the Spirit of St. Louis. Over

the past two weeks I discovered six more heroic adventurers—each

more adventurous, I might add, than the first two put together.

Wow! What a story!

I read it shortly after it came out in paperback, so maybe 1953 or 54? Fascinating. I also have the paperback of The RA Expedition, which I remember little about.

ReplyDeleteI haven't read any of the subsequent books, either, Rick. Heyerdahl says in the 1984 foreword that his 800-page American Indians in the Pacific: The Theory Behind the Kon-Tiki Expedition should satisfy any skeptics that the modern Polynesians originated in Peru. Probly a tad too scientific for me. I'm satisfied with the evidence he presents in Kon-Tiki.

DeleteAnd I suspect that the Polynesian sailors managed to make landfall in South America as they made their way around the South Pacific from the islands of and around New Guinea and New Zealand, interacted with the natives of South America who were probably mostly descended from emigrants from East Asia and migrants who made their way trhough North America however deliberately, and the Polynesian sailors (and perhaps with some Continental fellow-travelers among them) picked up some eventually-Chilean signifiers in that exploration and interaction. Rather than the Polynesians being descended, for the most part, from South American native cultures.

ReplyDeleteThat was the orthodox theory Heyerdahl wanted to disprove, and this book persuades me that he did (not that I have any intention of doing a doctoral thesis on the topic).

Deletehttps://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-voyage-kon-tiki-misled-world-about-navigating-pacific-180952478/

ReplyDeleteI saw the headline when I did my Google search. Counter-revisionists always find a way to slap down any challenge to orthodoxy. I haven't read Heyerdahl's 800-page American Indians in the Pacific: The Theory Behind the Kon-Tiki Expedition, but I would if I had to--if I chose to read the Smithsonian piece, which I have no intention at the moment of doing.

DeleteMatt, the genetic analysis that wasn't available at the time of Heyerdahl's work puts the kibosh on his notion that Polynesians generally were descended from South Americans; science, being a human endeavor, has problems with turf-protection and the like, but orthodoxies, as you put it, fall all the time in the face of the best evidence...and being Team Thor doesn't get one anywhere if the observed facts don't support his hypothesis as well as they do another--it's more than enough that he and his colleagues bravely demonstrated that interaction between the Polynesians and South Americans was possible at some level. In the early '60s, the most common view of geology among geologists and interested observers, for example, found the hypothesis of plate tectonics rather outlandish...which didn't stop this model which incorporated and explained observed facts from becoming an almost universally-accepted theory by the decade's end. Heyerdahl didn't prove to be mostly right. Neither did Galileo, who was ready to endorse a Sun-centered universe. Didn't make them any less important or valuable in their work. Just not actually correct, and not simply politically incorrect for the times.

DeleteI appreciate your diligence here, Todd, but, as I tried to make clear as civilly as possible, I don't really care. "Experts" love to disagree, and are especially adept at marshaling evidence to support their theories. I present exhibit B in defense of my nonchalant skepticism (and I know you have a relatively low regard for The Atlantic, but I'm less interested in the pedigree of the publication than in the articles within ;) ): https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/06/how-to-predict-the-future/588040/

Delete"Experts" might well do...and you as most of us lend credence to the "experts" you trust here and in every other area of life, Matt...a nonchalant skeptic isn't going to buy Heyerdahl's theory nor the argument of the ATLANTIC essayist (which seems disproportionally based on the intentionally alarmist predictions of Paul Ehrlich, not exactly an "orthodox" scientist nor expert) any more readily because their "experitise" agrees with what said skeptic would like to believe...but Heyerdahl's finding that it was possible to drift-sail to Polynesian islands from South America certainly doesn't prove that all the Polynesians are descended from South American natives, as the engaged skeptics of anthropology and archeology might note if you weren't trying to dismiss them out of hand as fuddy-duddies at best. And the pedigree of a magazine such as THE ATLANTIC is based on the quality of the articles it contains...which is why I liked it a lot in the late '70s and early '80s, even if the cover story on the first issue I bought was Claire Sterling's questionable "The Terrorist Network", and don't respect it much today.

DeleteThe scientific method is indeed one of marshaling evidence, usually through experimentation and repeating the experiments to see if the same result occurs. I won't try to make you care about why the results of investigation don't support Heyerdahl's theory, but don't understand why my opinion of the current ATLANTIC or suggesting that Heyerdahl's notions were ultimate incorrect for the most part is simply pesky attempts at oppression rather than a discussion of how things have gone since the Kon-Tiki experiment, or how much the ATLANTIC is fond of bootlessly fashionable stances these years...

I'm not a scientist or a philosopher, Todd. I like a good story, preferably with at least a little humor, and good writing, usually in that order. I'll pay attention to the voices of "experts" if they seem to have a bearing on my and my friends' health and safety. I'm aware the most powerful motivator in our lives is perception, and that emotions feed perception more immediately--and thus more dangerously--than cognitive reasoning. I guess this is why story and voice move me more than pure logic (which my lawyer dad taught me can be used by sophists to prove damned near anything, such as determining what the definition of "is" is. I like the story of Kon-Tiki. The reason for Heyerdahl's mission is secondary to me. He believed he proved his theory, and his conclusions are persuasive in the context of the time he arrived at them. I'm even intrigued by theories the earliest Peruvians were extraterrestrial, which my walking buddy, who teaches college Spanish and has visited Peru several times, has planted in my imagination. And, as you know, I'm no aficionado of speculative fiction. And I doubt, no matter how much empirical evidence might ever turn up, we will ever know if anyone besides a single nut, killed JFK--or who, if anyone, ordered the hit. (I leaned toward Johnson at one point, and he's still not in the clear IMO). ;)

DeleteWell...for some readers (and writers), speculative fiction helps inoculate them from being susceptible to outlandish ideas...since they are used to playing with them as fictional conceits...sadly, for some, this works less well...I'm definitely an Occam's razor kind of guy, and always have resented the Van Danikens...and did you ever read Paul Krassner's "The Parts Left Out of the Warren Report"? Clinton would've enjoyed arguing his way out of what's jokingly suggested there...

DeleteI've read precious little sf, altho have enjoyed what I read. Not sure why it never took off with me. Maybe because I'm nowhere near as well-read as I like to pretend.

DeleteGlad you enjoyed this book, Matt. Not my kind of reading, but who knows, maybe someday.

ReplyDeleteIf I had to bet, Tracy, I'd put my money on your liking it--a lot! :)

Delete