After a fitful ride on Last

Bus to Woodstock

I

doubt I shall read anything more by Colin

Dexter. Ever again. I can't remember when a book has disappointed

me—angered me—as much as this first in Dexter's thirteen-book

series of Inspector Morse crime novels. I admit it would be

convenient to put the blame on someone other than myself for steering

me there, but I can’t. Not even my crime-blogging friends, whom

I’ve let persuade me to try authors I’d never heard of. Nope, not

this time. I’m stuck with it. Taking a cue from Jimmy Buffett’s

Margaritaville, it's my own damned fault.

I say this by way of

cautioning readers who enjoyed the TV series based on Dexter’s

characters: Inspector Morse, its spinoff sequel

Inspector Lewis, and its prequel, Endeavour (which is

Morse’s first name). I haven’t yet seen any of the Morse

series, but I’ve watched some episodes of Lewis, and of

Endeavour, and enjoyed

them immensely. Ordinarily if I like a film based on a book, I’ll

give the book a shake. And I’ve found more often than not the

original’s even better than its screen adaptation, or at least is

engaging and entertaining in its own way. This was the case with the

Inspector Gently TV series. The lead character in Gently

Does It, the first of Alan Hunter’s forty-six books

featuring the North British detective, was quite different from the

TV Gently. It took some getting used to, but I enjoyed the read. Not

so with Last Bus to Woodstock,

which presents Inspector

Morse as an unintentional (I’m guessing) parody—something as

unpleasant to imagine as, say, Adam Sandler portraying Sherlock

Holmes.

|

| Kevin "Lewis" Whately" and John "Morse" Thaw |

I should note that while

the author handled the murder mystery competently, worthy of the TV

series, his detective is boring and arrogant. Morse treats his

assistant, Sgt. Lewis, with such contempt I felt at times like

reaching into the story and slapping the feces out of Morse. In a

bar, for example, while the two are interviewing witnesses in the

murder of a young woman found outside with her head bashed in, the

bartender offers Lewis a beer. “He’s on duty,” Morse snaps, but

accepts a drink himself.

In fact, it appears Morse is a

delusional lush. Sitting in his office, “mildly drunk,” he

believes he’s gaining some insight into the case. “His

mind grew clearer and clearer. He thought he saw the vaguest pattern

in the events of the evening of Wednesday, 29 September. No names–no

idea of names, yet–but a pattern.” Yeah, right.

At

another time, stuck at home

recuperating from an injury to his foot from falling off a ladder,

Morse bores Lewis with rambling theories about the case, not allowing

Lewis to comment or question anything he says. “A quarter of an

hour later a bewildered sergeant let himself out of the front door of

Morse’s flat. He felt a little worried and would have felt even

more so if he had been back in the bedroom at that moment to hear

Morse talking to himself, and nodding occasionally whenever he

particularly approved of what he heard coming from his own lips.

“‘Now

my first hypothesis, ladies and gentlemen, and as I see things the

most vital hypothesis of all–I shall make many, oh yes, I shall

make many–is this: that the murderer is living in North Oxford...”

In fact, Morse has no evidence at all for this or any of his

other screwball assumptions. I found myself screaming silently at one

point, and suddenly bursting out laughing, as the long-suffering

Lewis, the author tells us, “wished he’d get on with it.”

|

| Kevin Whately |

Another

thing I found annoying was

the multiple-viewpoint narrative. We’re inside the heads of most,

if not all (I didn’t keep track) of the suspects, which, I know, is

a perfectly valid literary device, but for me it doesn’t work in a

mystery—or at least in this mystery, as the characters are

stereotypes, thus less interesting than had they remained mysteries

themselves, known only through the detectives’ sensibilities. In

Last Bus to Woodstock

none of the characters whose heads I was allowed to enter aroused my

suspicion, despite some clumsy “clues” tossed my way. This left

as likely suspects the few I knew only as Morse knew them. Presumably

a craftier writer could bring off having a character we feel we know revealed

as a surprise in the end as the murderer, but I cannot recall an

example where such was the

case, other than in a straight procedural plot.

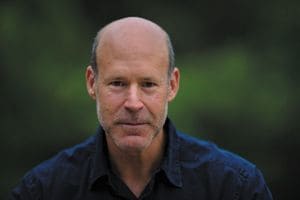

|

| Colin Dexter |

I

found the setting interesting—Oxford and its academic environs.

Several minor characters are academics, and we get much byplay in

this milieu—credible because of Dexter’s background as a classics

teacher. I bought a three-book collection with my Kindle download.

Unless I experience a brain transplant or a metaphysical change of

heart, I shall not be reading either of the other two.

But

I do intend to borrow the public library’s Morse/Lewis DVDs. I know

they’ll be good!

[For

more Friday's Forgotten Books check the links on Patti

Abbott's unforgettable blog]