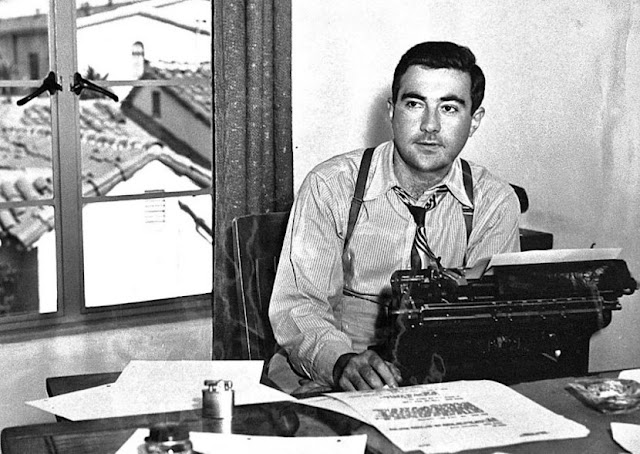

Your

name is David Goodis. You’re a guy who lives on luck, whose only

talent is stringing

words together.

Your streak of shitty luck, capped by your wife of two years dumping

you last year, might be turning around. Your second novel will soon

hit the silver screen with Bogie and Bacall. Time to celebrate. Then

again, luck is fickle. You need to bang out another novel. Quick. Why

not another dark one, like the lucky one, another Dark

Passage?

Maybe dark is your metier.

You’re

in a bar. A dark bar. You’re in a booth in a dark corner trying to

come up with an idea for your next

novel while

lady

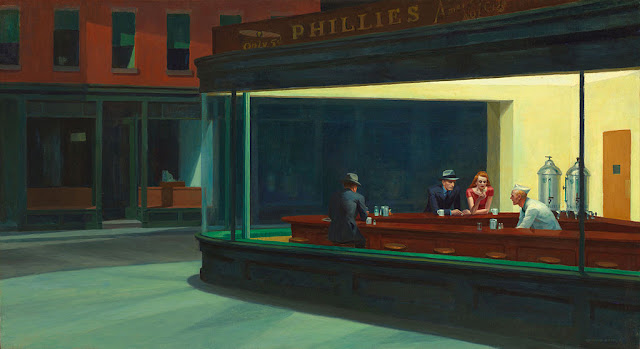

luck’s still hanging around. There’s a painting on the wall. A

painting of a diner. The diner is well lighted inside but in a dark

part of town. Only three people are inside, plus the man behind the

lunch counter. The three customers seem lost in thought. It feels

like a lonely place. You take out your notebook and write these

words:

The

place was well off Fourth Street, and the weak yellow light from its

window was the only light on the narrow street. Vanning took her in

there and they sat at a small table near the window. They were alone

in the place. It was very small. Their waiter was the proprietor, and

he was a man who looked as if one of his own meals would do him a lot

of good. He was trying to be friendly, but weariness prevented him

from getting it across. He took their order and went away.

You

work out some ideas in your head. Write more words in your notebook.

You finish your gin rickey. You have another and you jot down notes

until you finish the drink. Then you walk back through the hot sticky

night to your lonely apartment. You sit down at your typewriter. You

insert a fresh sheet of paper into the machine. You stare at the

blank page. You look through the notes you made in the bar. You take

a deep

breath, nodding your head a couple of times, and you type:

It

was one of those hot sticky nights that makes Manhattan show its age.

There was something dreary and stagnant in the way all this syrupy

heat refused to budge. It was anything but a night for labor, and

Vanning stood up and walked away from the tilted drawing board. He

brushed past a large metal box of water colors, heard the crash as

the box hit the floor. That seemed to do it. That ended any

inclination he might have had for finishing the job tonight.

Heat came into the room and

settled itself on Vanning. He lit a cigarette. He told himself it was

time for another drink. Walking to the window, he told himself to get

away from the idea of liquor. The heat was stronger than liquor.

He stood there at the window,

looking out upon Greenwich Village, seeing the lights, hearing noises

in the streets. He had a desire to be part of the noise. He wanted to

get some of those lights, wanted to get in on that activity out

there, whatever it was. He wanted to talk to somebody. He wanted to

go out.

He was afraid to go out.

And he realized that. The

realization brought on more fright. He rubbed his hands into his eyes

and wondered what was making this night such a difficult thing. And

suddenly he was telling himself that something was going to happen

tonight...

Your

fingers fly across the keyboard. Ten thousand words a day. You have

the title by the time you type He

didn't even blink when he heard the sirens, although he knew they

were coming toward him and toward no one else. The End

You’re

pleased with

Nightfall.

You know it has flaws. The ending’s not as dark as the other one.

You’re thinking Hollywood now. Hollywood’s not ready yet for as

dark as you want to go. You know Dark

Passage

was a lucky fluke. But Nightfall’s

got the same milieu. That Edward Hopper loneliness. It’s got

suspense and characters and snappy dialogue.

Yeah, the flaws. Dialogue’s

all one voice. Interior and spoken for the two viewpoints. Spoken for

everyone else. You don’t know women very well. You make them either

very very good or horrid. Haha. Like the nursery rhyme. But sometimes

you make them so it’s hard to tell. Like Irene and Martha.

You write roughshod over facts

sometimes. Like with the plot. You know police in three states

wouldn’t care much if Vanning shot a criminal or that he might have

hidden $300,000 from a bank robbery or that they’d compare

fingerprints they found on the gun with fingerprints he gave when he

bought a car. Fingerprinted to buy a car bwaaahahahaha. You laugh at

that shortcut fiction because you know your heart-grabbing characters

and breathless suspense and the desperate surreal mood you’ve

created will carry your thrill-junky readers as far as you wish to

take them. Farther than the Lone Ranger and Dingus Magee and

Bogie/Bacall and the Fat Man all in one crazy wild-ass bunch and you

know it.

And

even tho you have a j-school degree and know damned well no newspaper

reporter would dream of calling the Denver PD from New York from a

pay phone to find out everything the police in two states know about

a nearly year-old homicide and missing three-hundred grand the

Seattle bank’s already recovered from its insurance company and get

the Denver police to call the Seattle police while you’re waiting

in the phone booth and for Denver to relay Seattle’s information

back and...hello? Hello...clickclickclick...But

you shrug and laugh and make Vanning impersonate a reporter and

his editor and get the information this way because your flying

fingers and ten-thousand-word daily self-imposed deadline and the

story’s furious pace and Hollywood’s insatiable maw and Bogie and

Bacall simply won’t allow you to do it the long way.

You

pause for part of a second to field a notion that maybe there’s a

chance for a spinoff series starring Vanning as the greatest news

reporter who ever lived who wins so many Pulitzers he gets bored and

drinks himself to death and...But back to Nightfall.

Stop with the damned distractions!

And

you write paragraphs like this and holy shit you’ll have your

readers drooling on the page:

...he saw himself in a mirror,

this time the mirror behind the bar, and he saw in his own eyes the

expression of a man without a friend. He felt just a bit sorry for

himself. At thirty-three a man ought to have a wife and two or three

children. A man ought to have a home. A man shouldn't be standing

here alone in a place without meaning, without purpose. There ought

to be some really good reason for waking up in the morning. There

ought to be some impetus. There ought to be something.

Postscript:

You die a couple of days following a bar fight nineteen years after

publishing Nightfall.

You were 49. You’d written 14 more novels, many of them inspiring

movies (most of them in France) or TV segments. The film

adaptation of Nightfall

was released in 1956, nine years after the book, and without Bogie or

Bacall. Your books go out of print but have rebounded and are bigger

than ever, riding a revival wave of noir. You’ve become a genre

classic. That’s something.

[For

more Friday's Forgotten Books check the links on Patti

Abbott's unforgettable blog]