I’m

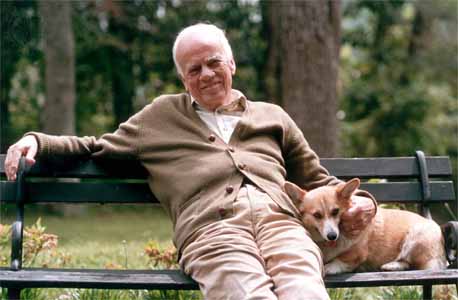

thinking now I should have re-read Walker Percy’s six novels in the

order they appeared, and I’m trying to understand why I chose to do

it randomly. It’s just occurred to me I might have started the

re-reads the way I started the first-reads---at least at first. The

Moviegoer

appeared first, and I read it first and have no recollection what

drew me to it. I’ve since read it twice more, most recently three

years ago before I decided to read the other five again, as well. I

recall that

years after reading Moviegoer

a

reporter colleague at the newspaper that employed us recommended

either The

Last Gentleman

or The

Second Coming,

and I read the one she suggested, which hooked me so thoroughly I

then read the others on my own, as well as articles and interviews

and Percy’s nonfiction books.

This time

around my

Percy reading

hopped to

and fro

until I came to the two my colleague recommended decades ago. I chose

The

Second Coming

because at this point I remembered enough of it to know it was my

favorite of them all, despite the fact it’s the sequel to The

Last Gentleman,

which I intend to read next, and finally, one more time, The

Moviegoer.

There. That

said (I hate that expression), I remembered liking Coming

best because of the protagonist’s quirky romance with a young woman

he discovers while hunting an errant golf ball in a woods near his

home and abutting the golf course. I almost wrote “literally

stumbles upon” because he’d been falling down of late, and

possibly had fallen again in the woods moments before he finds her

living in an abandoned greenhouse there. I don’t remember all of

the falling down episodes other than that most of them occur on or

near the golf course. He’s approaching middle age and experiencing

the existential (psychological and philosophical) torments

characteristic of Percy’s male characters, and the young woman has

escaped from a mental hospital.

The

Second Coming

was described in a Christian Science Monitor review as “a

comedy shot through with serious observations.” That’s a fine

description, which I could have paraphrased without crediting its

author, Elizabeth

Muther,

but I wanted an excuse to link you to her review, which is better

than anything I might write here. (It’s not that I’m humble,

just...well, I think it’s dumb to try to reinvent wheels that have

been around thirty-seven years by people who invent such things for a

living. So I won’t do a plot synopsis or a philosophical analysis

of Coming

or rave about Percy’s cleverly satiric approach to his favorite

theme:

the search for meaning in a social culture that stifles individual

awakening in a hothouse atmosphere of stale routine and expectations,

other than to note that his caricatures of moneyed Southern

archetypes are either dead-on or seem so because he’s such a damned

good writer and the only vivid exposure I’ve had to moneyed

Southern archetypes is from his damned good writing—even though

I’ve lived in Virginia for nearly half a century.)

That said (Jesus, I hate that

expression!), what drew

me to Coming

this time was the recollection of the romance between the

falling-miserable-moneyed-slowly-going-nuts protagonist (with whom I

identified—as always) and the

nubile-amnesiac-slowly-exhibiting-sanity greenhouse dweller who hits

it off with him (me). I’m discovering more and more that my

long-held notion of being an encrusted, oh-yeah cynical newsman was

something of a sham and am trying to hang

onto at least some of

that protective illusion by resisting my subliminal, puerile romantic

inclinations inch by hard-fought inch, yet I enthusiastically gave

myself a mulligan on this one, because, well, it’s Percy, what the

hell. (And the girl “smells good.”)

I always give you, my faithful

readers, a quote or two to both stretch out these reports a tad to

make room for the illustrations, as well as to give you a taste of

the author’s style. Writers are always told to “show, don’t

tell,” so instead of telling you, as do most of the professionals,

about an author’s craftsmanship, wit, grace, what have you, here’s

a typical sampling. It not only covers all of the bases mentioned in

the above sentence, it addresses an aspect of Percy’s work that

invariably appears in critiques of his work, i.e. his Roman

Catholicism, to which he converted and defended eloquently ever

since. He keeps it sly and indirect in his fiction, and is not afraid

to poke a little fun at the religious. Here’s what I mean:

“IT WAS A

FINE SUNDAY morning. The foursome teed off early and finished before

noon. He drove through town on Church Street. Churchgoers were

emerging from the eleven-o’clock service. As they stood blinking

and smiling in the brilliant sunlight, they seemed without exception

well-dressed and prosperous, healthy and happy. He passed the

following churches, some on the left, some on the right: the

Christian Church, Church of Christ, Church of God, Church of God in

Christ, Church of Christ in God, Assembly of God, Bethel Baptist

Church, Independent Presbyterian Church, United Methodist Church, and

Immaculate Heart of Mary Roman Catholic Church.

“Two

signs pointing down into the hollow read: African Methodist Episcopal

Church, 4 blocks; Starlight Baptist Church, 8 blocks.

“One sign

pointing up to a pine grove on the ridge read: St. John o’ the

Woods Episcopal Church, 6 blocks.

“He lived

in the most Christian nation in the world, the U.S.A., in the most

Christian part of that nation, the South, in the most Christian state

in the South, North Carolina.”

The title?

Oh, that. Percy and I (via his protagonist, Will Barrett) have a

little fun with the biblical notion of End Times. Nothing serious...I think.

|

| Nah...? |

[For

more Friday's Forgotten Books check the links on Patti

Abbott's unforgettable blog]