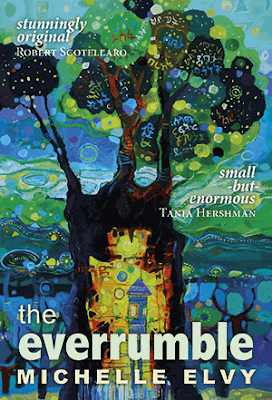

One of the

many beauties of The

Everrumble

is its overt

independence

from sequence, without

confusion.

I

don’t recall previously reading a novel in which events hop around

the calendar so willy nilly. Yet,

in retrospect it

is obvious the subtext of

Michelle Elvy’s short novel (132 pages)

has its own linear integrity

corresponding

neatly with the awakening curiosity for an idea so unusual and subtly

crafted there are moments one must remind oneself to breathe.

Everrumble’

s

ingeniously compressed story spans all 105 years of Marjorie Hanna’s

life—from her very first gasp to her final, silent thought. The

name “Marjorie Hanna” has now appeared twice as many times in

this review as it does in the novel. I include it here only to give

to Zettie a conventional perspective, however fleeting, as she may

well be the oddest human being ever portrayed in literary fiction.

The name

“Zettie” comes

about on Marjorie’s second birthday. Her Aunt Zettie has

given her a blanket. During the birthday festivities Marjorie’s

five-year-old brother Brent

“pointed back and forth between Auntie and his sister and said, Big

Zettie, Little Zettie. Little

Zettie wore the blanket on her head all day and

the name stuck.” Five years later, on her seventh birthday, she

makes two decisions:

to talk no more, for any reason, and to stay under the blanket, where

she spends the rest of the year.

She

spends the rest of her life living richly and wondering at the

special gift she’d accepted at birth. On her last day, ninety-eight

years after she stopped talking in order to listen to the sounds no

one else could hear, understanding comes to her.

“The moment of clarity comes in the morning, and it is later in the

day, just before the rapid darkening that is the tropical night, that

she will die.

“It’s

not so much a vision as a full-on worldly orchestral movement.

Overtones and undercurrents. Chantings and crashings. Rowdy and

dreadful but also melodious and beautiful. It happens in a flash,

yes, but its layers are as deep as oceans, as wide

as the space between stars...”

Her

special gift arrives at the moment of her birth. A screaming no other

person in the world hears. It

drifts

in through the open hospital window and vibrates

her timpanic membrane. Of

course the newborn

has

no way of identifying this

sound, because

“how

can you identify anything over the suckingslurpingslipping

surroundsound of your own

birth?”

Soon other sounds reach her. A

bee buzzing across town in a garden, a toad croaking in a pond miles

away, someone coughing on the other side of the world. At age five

she senses these sounds seek her out, and she does her best to

listen. But there’s something else besides the random buzzes and

voices that reach her ears. It’s a

low rumble.

“It

bores gently into her ear and winds down the canal, vibrating through

her whole body, her throat, her chest, her tummy. It moves out to the

tips of her limbs, to the very ends of her long brown hair. Once she

hears it she can’t un-hear it.

“The

rumble is here to stay.”

We

peek in on Zettie at different stages of her life. By age twelve

she’s learned to narrow her focus on the origin of individual

sounds. Hearing a mosquito flying through a broken screen three

streets away, she counts the wingbeat: 111 times per

second.

At

fifteen, her uncle forces

himself on her. She knew he trusted she wouldn’t talk.

Her silence follows him. To his job, to his weekly poker game, and

when he dies three years later she hurls her silence at him “one

last time, screaming down his ear.”

Once

she stops talking, the

absence of verbal

distractions heightens

Zettie’s

other senses, especially her

ability to concentrate. Words fascinate her. She reads

widely, goes to college,

studies languages, graduates with high honors. She still doesn’t

speak the languages, but she understands them, and makes a career of

translating new editions of literature. She travels widely, living

here and there, never staying more than a few years in any one place.

She marries and has two daughters. She and her husband eventually go

their separate ways. She raises their daughters alone.

but maintains “a loving

distance relationship” with their father.

In

a journal she notes the only time she wanted to speak aloud was to

read to children. This was before her daughters were born, and we do

not know if in fact she read to them when they were small. Presumably

not, because surely that would be a highlight in her story, and we

are not privileged to know. I do know Zettie, though, feel I’ve

known her all her life. And I feel she knew me, as well. She knew us

all, one way or another. At the very end we learn what she concludes

of

the

everrumble:

“The

heartbeat of every living creature.” So

loud it hurts

her ears. “They’ll soon

start bleeding. And why not? Her form will turn to liquid, then dust.

Blood is just blood. It’s nothing. It’s nothing.

“Her

skin is dancing. Telling the story of the world.”

Michelle

Elvy is an editor and widely published writer of poetry, fiction, and

creative nonfiction. The

Everrumble

is her first novel. She

lives in New Zealand, and is an avid sailor.

No comments:

Post a Comment