I’ve been making the mistake

lately of reading professional reviews after reading the book rather

than before. This despite knowing that reading reviews in advance of

the book gives me insight that enhances my appreciation of the

book—which is one reason for publishing reviews in the first

place. The main reason, of course, the one directly related to

publishers sending reviewers free “review copies,” is

to help sell the book. So what in hell am I doing writing this review

sixty-six years after Pnin,

was published? Did the publisher’s free review copy get lost in the

mail for more than half a century? Well now waitaminute, weren’t

those the Pony Express days? Maybe the damned thing’s still

bouncing around in a saddlebag out on a prairie somewhere in

Nebraska. I mean, if so, it shouldn’t be held against me if

I couldn’t wait any longer. I’m a patient man, but...there are

limits! So I downloaded the Kindle version, costing me, btw, probly

six times what I’d have had to pay had I bought it back in those

Bill Codyish days of yore. Was I what? Alive that long ago? Well now

hey, some cards a reviewer’s allowed to keep face down,

n’est-ce-pas?

[rhetorical question--move along, please!]

Anyway, not all is lost. There

are advantages to reading a review by a reviewer who’s literally

been left in the dust. Same as there are, say, to buying a

road-gripping Armstrong tire, created eons after the original log

wheel rolled away from its inventor’s flint adze. In the situation

of Pnin, the reader has instant online access to the insights

of top-line literary critics, which, by my failing to deepen my

appreciation of this short, classic novel by first reading them, and

which, by my coming to them after the fact, humiliated my intention

of doing a proper review for you here, have unwittingly freed me to

narrow my focus to only one facet of Vladimir Nabokov’s break-out

American literary achievement. That one facet, which counterbalanced

the ungainly, gentle, laughingstock

persona of Timofey Pnin—pronounced Pun-in by Pnin in the

novel, but which one reviewer has insisted is P’neen--the,

Soviet Union escapee-cum-teacher of Russian literature. The one

saving grace: tragic romance. Yes, that resonantly soulful

Russian literary tradition. Pnin’s Mira plucks the balalaika

heartstrings with a poignancy on a par with Zhivago’s Lara.

“In order to exist

rationally,” our anonymous narrator tells us, “Pnin had taught

himself, during the last ten years, never to remember Mira

Belochkin—not because, in itself, the evocation of a youthful love

affair, banal and brief, threatened his peace of mind (alas,

recollections of his marriage to Liza were imperious enough to crowd

out any former romance), but because, if one were quite sincere with

oneself, no conscience, and hence no consciousness, could be expected

to subsist in a world where such things as Mira’s death were

possible.”

The slightest reminder of his

long-lost Mira, in the midst of giving a speech, for example, can

divert him into a split-second reverie of a past encounter.

Our narrator, who

incrementally reveals his acquaintance with Pnin from childhood,

mentions his first sighting of Mira at an amateur play some

youngsters, including Pnin, held in an old barn. Without naming her

then, he remembers her as a “pretty, slender-necked, velvet-eyed

girl,” the sister of a mutual acquaintance.

Pnin last saw her in a Berlin

restaurant after she escaped the Soviet Union and before her arrest

by Nazis. “They exchanged a few words, she smiled at him in the

remembered fashion, from under her dark brows, with that bashful

slyness of hers; and the contour of her prominent cheekbones, and the

elongated eyes, and the slenderness of arm and ankle were unchanged,

were immortal, and then she joined her husband who was getting his

overcoat at the cloakroom, and that was all—but the pang of

tenderness remained, akin to the vibrating outline of verses you know

you know but cannot recall.”

He

learned years later, after escaping to the United States, that Mira

had been murdered

at Buchenwald.

More

recently, in one of his unbidden remembrances, musing at night alone

on a porch, “...again the clumsy, shy, obstinate, eighteen-year-old

boy, waiting in the dark for Mira—and despite the fact that logical

thought put electric bulbs into the kerosene lamps and reshuffled the

people, turning them into aging émigrés and securely, hopelessly,

forever wire-netting the lighted porch, my poor Pnin, with

hallucinatory sharpness, imagined Mira slipping out of there into the

garden and coming toward him among tall tobacco flowers whose dull

white mingled in the dark with that of her frock...

“Pnin

slowly walked under the solemn pines. The sky was dying. He did not

believe in an autocratic God. He did believe, dimly, in a democracy

of ghosts. The souls of the dead, perhaps, formed committees, and

these, in continuous session, attended to the destinies of the

quick.”

While

Mira lives

in his heart, Pnin marries

Liza, a restless temptress who doesn’t

hang around long. His

sense of her as he watches her leave is a mixture of reluctant

acceptance and relief:

“He

saw her off, and walked back through the park. To hold her, to keep

her—just as she was—with her cruelty, with her vulgarity, with

her blinding blue eyes, with her miserable poetry, with her fat feet,

with her impure, dry, sordid, infantile soul. All of a sudden he

thought:

If people are reunited in Heaven (I don’t believe it, but suppose),

then how shall I stop it from creeping upon me, over me, that

shriveled, helpless, lame thing, her soul? But this is the earth, and

I am, curiously enough, alive, and there is something in me and in

life—“

He

breaks down when his friend Joan, hoping to console him, asks softly,

“Doesn’t she want to come back?”

“Pnin,

his head on his arm, started to beat the table with his loosely

clenched fist. ‘I haf nofing,’ [he]

wailed...between loud, damp sniffs, ‘I haf nofing left, nofing,

nofing!’”

What

we

have is something marvelous. An all-too-human character brought alive

for us in all his dimensions by an enchanting writer, with the bonus

of an intimate look at a

small

college community of Russian émigrés

in the early 1950s portrayed with

precision, fictionally,

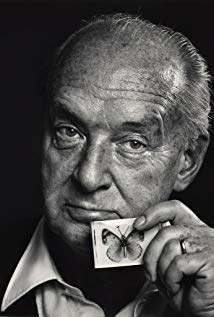

by one of their own. Nabokov is best known for Lolita,

his startling, controversial novel about a middle-aged man’s

infatuation with a 12-year-old girl. Pnin,

however,

was his break-out in U.S. literary circles, initially appearing as a

series of individual

stories in The

New Yorker.

Its success, establishing

his reputation as a writer of uncommon brilliance, helped persuade

publishers to take a chance with the more risky Lolita.

|

| Vladimir Nabokov |

Below

are links to a couple of comprehensive reviews of Pnin:

Charles

Poore, The

New

York Times