Were

Hoke Moseley a cop in the rural South it could be said of him, Thet

boy’s inna heapa trouble, son (the “son” thrown in just for its

sound). The list of his troubles is so long I’m liable to forget

one or two, or more, but I’ll start with the most obvious:

he’s a homicide

sergeant

in Miami living in a dump hotel outside his department’s

jurisdiction. As he tells his two teenage daughters, who’ve dropped

in unexpectedly on him (another of his troubles), “South Beach is

now a slum, and it’s a high-crime area, so I don’t want you girls

to leave the hotel by yourselves. If you had a doll, and you left it

out overnight on the front porch of the hotel, it would probably be

raped when you found it in the morning.”

He

has two weeks to find a permanent domicile within the jurisdiction,

or risk losing his job. Problems three and four are directly related

in a cause/effect way. He’s living in the dump hotel because he has

to send every other monthly paycheck to his ex, which doesn’t leave

him enough to afford a place in the city. The daughters’ arrival

removes the initial financial burden of the divorce, but now he must

find a place suitable for himself and

the girls and

Ellita

Sanchez, his

new unmarried Cuban partner whose father has kicked her out of the

family home after

learning

she was pregnant (not by Hoke—he’s

smarter

than that).

And

let us not forget, Hoke and Sanchez

and his former partner, Bill Henderson, have murders to solve. Lots

of them.

Most

immediately for Hoke and Ellita is the death of a young junkie of an

apparent overdose of high-quality heroin. Hoke suspects foul play,

however, plus he’s taken with the junkie’s attractive and

flirtatious stepmother. While probing into the death, and weighing

the fact he hasn’t had sex in four months, he cautiously proceeds

to woo the woman. Meanwhile,

there are fifty cold homicides the trio has been given two months to

solve. Take a moment, please, to absorb the implications of this

phenomenon.

Fifty

cold cases (providing

the novel’s title, New

Hope for the Dead).

The

case files were compiled

by Major Willie Brownley, who hopes cracking a few of these old

murders will help elevate him to one of eight colonelcies the new

police chief says he wants to create in lieu of pay increases. One

might think Brownley’s a stereotypical administrative jerk for

harboring this ambition, but he’s really a pretty good boss. He’s

the department’s first black major, and he figures this could be

his last chance for higher rank before retirement. “I didn’t

become the Homicide chief because I was a detective,” he tells

them, after assuring them he trusts their judgment as to which of the

old cases they have the best chance of solving. “I’m an

administrator, and I was promoted for my administrative ability. It

didn’t hurt that I was black, either, but I wouldn’t have kept my

rank if I couldn’t do the work.

“It

seems to me, if we can solve some of these cold cases, it’ll make

our division and the entire department look even better than it is.

And if that happens, they’ll have to make at least one of those new

colonels a black man. What I want is one of those silver eagles and

another gold stripe on my sleeve.”

The

team gets off to a great start, making progress on two of the cases

within a couple days. The first, when Henderson on his way to lunch

spots the suspect known as Capt. Midnight. The second when Sanchez

interviews a woman who claimed to have seen a girl whose bloody

clothing was found in a field some three years earlier. The witness

had changed her story with the male detective trying to interview her

at the time, and was written off as a “man hater.”

This

is the second of the Hoke Moseley series I’ve read. I’m hoping to

read the rest of them in sequence. I am totally hooked on the

character and on author Charles Willeford’s droll, yet realistic

voice. I was

enormously impressed by Willeford in my review of the first in the

series, Miami

Blues,

and see no need to restate the kudos here, although I can quote a

line or two from novelist James Lee Burke’s introduction to New

Hope for the Dead.

The two became friends while teaching at Miami-Dade Community

College:

“Early

on I became aware of his tremendous sense of humor, his wit, and his

ability to tell wonderful stories. But as I came to know Charles

better, I also began to realize his great reservoir of humanity, his

goodwill, his loyalty to his friends, and his modesty as a man, an

artist, and a decorated soldier.

“He

was one of the most extraordinary men I ever knew. He literally lived

history. He rode the rods when he was fifteen, lived in hobo jungles,

boxed as a club fighter, fought roosters, raised horses, enlisted in

the cavalry when he was sixteen, drove a tank in the worst battles of

the Bulge, won the Croix

de Guerre,

the Purple Heart, and the Silver Star.”

|

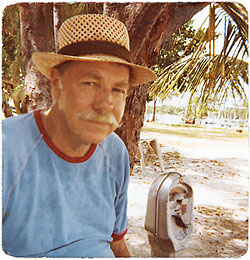

| Willeford |

I

would be remiss not to add this line from the New

York Times Review of Books:

“If you are looking for a master’s insight into the humid

decadence of South Florida and its polyglot tribes, nobody does that

as well as Mr. Willeford.” After two novels now, and this, I’ve

no desire to visit any part of Miami. Ever.

What

I find most seductive about Willeford’s writing is his attention to

detail. I don’t mean the kind of monotonous descriptions of

furniture and buildings and landscapes and clothing and such that

seems de

rigueur

for novelists these days, following the common dictum that it’s

holier to show than merely to tell. Not saying Willeford skimps on

these details. Not at all. I definitely felt I’d been plunged into

“the humid decadence of South Florida and its polyglot tribes.”

Even turned on the A/C in my apartment in case some of that South

Florida mugginess happened to migrate north while I was reading about

it. Nope. There’s enough of that de

rigueur

detail in the two Hoke Moseley adventures I’ve read thus far,

enough to stimulate my imagination to fill in the blanks. What I mean

by “seductive” detail, is his depiction of the

ordinary

things

his characters do that most novelists glide over in the interest, I

suppose, of keeping up a narrative tempo. The kind of pace The

Village Voice

says is “so relentless, words practically fly off the page.” I’d

say that’s a tad over the top. The words don’t “fly,” but

they move along without getting bogged down in literary correctness.

Here’s an example that doesn’t seem like much, but left my jaw

agape:

The

waiter brought the conch chowder and the oysters on a tray. He also

gave them silverware, wrapped in paper napkins. He placed Loretta’s

wine spritzer in front of her. Hoke poured the last of the beer into

his glass and topped it off with a head from the fresh pitcher. The

waiter put the empty pitcher on his tray.

This

comes during one of the most suspenseful

scenes in the novel. It’s a perfect glance

away from the building tension,

focusing on the simple mechanics of service in a restaurant. We’re

not distracted by the brand of beer or wine spritzer or how

the waiter is dressed or looked. Non-essentials, those. It’s the

way I imagine Hemingway might have portrayed the little scene, with

us knowing all the while the deadly potential lurking nearby, perhaps

only seconds away. “The

waiter put the empty pitcher on his tray.” A

cinematic moment. Extreme closeup on the pitcher, the waiter’s

hand, and then the tray. All the while the tick

tick tick

of something we know is coming.

Genius,

I would say. But maybe I’m just easy.

I do want to read some books by Willeford someday, Mathew, but I have worried that his books may be too dark and gritty for me. You do make his writing sound very, very good.

ReplyDeleteIt's astounding, Tracy. I don't cotton to dark and gritty if the voice is dark and gritty, trying to shock. Willeford's writing is so full of wry humor the dark and gritty has a transient feel, not inevitable. The Kirkus reviewer said of it, “Willeford has a marvelously deadpan way with losers on both sides of the law.” His humor doesn't seem planned or obvious. It's just the voice of someone who knows the dark side but prefers the light. You'd love the series.

Delete