Baffled

in Boston

was my prize for slogging through two rather awful—one really

rather awful—melodramatic crime/romance novels by Stephen Humphrey

Bogart, scion

of Hollywood's most iconic lovebirds. Besides alliteration, the only

Bogie/Bacall/Baffled

link I found in my several-day read-a-thon was the late Gary Provost,

author of Baffled

and presumed ghost-writer of Play

It

Again

and The

Remake: As Time Goes By,

both titles alluding to an unforgettable scene in Bogie's classic

film, Casablanca.

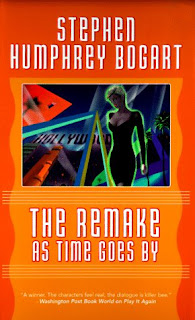

Provost

was a

novelist, author of true-crime and

how-to-write books,

and

a popular

writing

coach

whom

Stephen Bogart credits with assisting in the memoir Bogart:

In Search of My Father,

published in 1995. It

was

the same year Provost died, and

the same year Play

It Again

came

out—with only Bogart’s

name on the cover.

As

Time Goes By

followed two years later.

My plan was to compare Stephen

Bogart's two novels

with one of Provost's

for clues that Bogart's were ghosted or that maybe he had some less

visible help with his fiction, at least with the first novel. My

conclusion:

There's

no chance Provost or likely any other pro

wrote these novels. They're too green. Dialogue

stiff and overdone, and way too much telling instead of showing.

Frantic sex scenes like those in pulp magazines of the ‘50s. The

kind of callow crap

youngsters of my ilk

were reading and trying to imitate back then.

On the positive side, I

have a hunch Provost

helped plot and shape Play

It Again. The

technique is not new, but

it’s an effective suspense builder—italicized

sections from the serial killer's POV giving us insight "RJ

Brooks," the PI protagonist, doesn't have. The

first murder victim is RJ’s mother, the world-famous movie queen

obviously meant to be Stephen Bogart’s mother, Lauren Bacall. His

father, whom we know was Humphrey Bogart, who died when Stephen was

eight, appears only in memories of characters who see and hear him in

the spitting-image face and voice of his son. Essentially it seems

Stephen Bogart simply changed names and added fictional circumstances

for the novels.

Same

basic cast and same craft flaws for RJ’s later adventure, but with a silly,

meandering plot and a

nauseating romance

between RJ and a TV producer that began in the first novel and

curdles into soap-opera melodrama in The

Remake. I did get

one hearty laugh the author most likely did not anticipate.

The

serial murderer

is one of several characters, including RJ, who vehemently oppose the

tawdry

remaking of Casablanca

(called As Time Goes

By in the novel).

RJ is horrified that

the lead characters will be a brainless musclebound actor noted for

playing a lifeguard on TV, paired with a porn star known mostly for

roles she’s played nude

on her back. RJ spouts

sentimental outrage that the memories of his father and mother, who

starred in the original movie, would be outrageously cheapened by this ripoff.

He’s

a leading suspect in the murders, of course, which means it’s

pretty much up to him to find the real murderer. One of the suspects

puts out a Hollywood-insider magazine, where he has displayed his

murderous rage in print. “‘As

Time Goes By means something, Brooks.’ the

wheelchair-bound editor

tells RJ. ‘Something special, pure, good. Not just to me, but to

all of us, our whole culture. Millions of people, all around the

world. Because it stood for something. It was a rallying cry for the

last great moral battleground—and the good guys won. It was

important, goddammit—maybe one of five or six movies in history

that are really important.’

Okay,

Casablanca

did win three Oscars, including best picture, but...

My out-loud

laugh came before

I reached the editor’s tirade, as I tried

to imagine sultry sassy Bacall doing

Ingrid Bergman’s

peerless scorching of

Bogie’s cynical

heart, quietly wooing

Dooley Wilson to “Play

it, Sam. Play As

Time Goes By.”

Bacall would’ve been

sitting on the piano, her

husky voice caressing

the words, shapely leg

swinging, and

laughing eyes batting

at a Bogie so newly

smitten he’d have pushed a peanut across the floor with his nose to

prove how forgiving he was of

whatever little misunderstanding they’d had...when? Paris? Oh

hahaha...ce

n'est rien !

RJ in both novels can’t

settle on being a tough guy or melting at the thought of Casey

Wingate, who treats him like a stooge except when she suddenly starts

tearing his clothes off and biting his neck. Here he is in the second

novel, giving us his Bogie sneer:

“He liked the fact that all New Yorkers are predators. It was why

he lived here. He’d grown up with the sun-tanned, veggie-loving

mood-ring kissers on the West Coast, and he would just

as soon take the knife in the front,

New York style.” Okay, sounds

like something the old man might have said in a movie. Moments

later, though,

he’s begrudging media crews trying to take advantage of his

bloodline and resemblance to his famous dad:

“Wouldn’t say anything to anybody with a press pass. Except Casey

Wingate, of course. Casey. He

sighed just thinking about her.” What?

Sighing?

A

Bogart male? Oh

dear. Well, we can safely assume if anyone helped Stephen Bogart with

this book it sure as shootin’ wasn’t Norman Mailer.

|

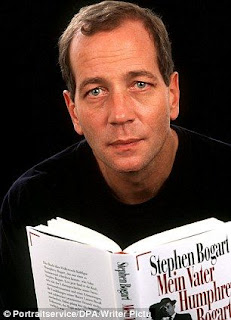

| Bacall, Bogie, and Baby Bogie |

Now

then I could see Mailer lending a line or two to the first one, Play

It Sam, such

as the following media-baiting scene sans Ms. Wingate:

“With a block to go he’d had enough. He stopped walking and held

up a hand for quiet. ‘Ladies and gentlemen! Please, just a moment,

ladies and gentlemen!’ They didn’t exactly get quiet, but they

got quieter. When R.J. felt that all eyes were on him, he took a

breath and looked squarely into the nearest camera. ‘Blow it out

your asses,’ he said and turned to go.”

That’s

my boy, I can hear Bogie lisp. Precisely

the kind of breezy irreverence leavening Provost’s

ill-fortuned-but-plucky protagonist of Baffled

in Boston,

which opens thusly:

“On

her way out the door my wife, Anne, said something about my choice of

the freelance writing life being irresponsible, selfish, and unmanly.

My unwillingness to wear a necktie was childish. My trips to Las

Vegas were reckless. And most of her orgasms had been faked. Clearly,

she was peeved. I was, she said, an utter failure. Also, she had

fallen in love with another man, so she thought it would be best if

she left me. It would turn out to be the second worst thing that

happened that week.”

Marvelous

beginning. I’ve read it five times already, and am

tempted this instant

to go back and savor it once again. Had

I written it I’d be standing on some street corner in Manhattan

right now belting it out to passersby, and not especially caring

whether or not they dropped any bread in the hat at my feet. Hell,

I’d

sell my pet skink to the Gypsies if they’d align the stars to

enable me to write

a

paragraph

half as good. I’m beginning to think this is how Stephen Humphrey

Bogart tried to learn to write fiction, reading incredibly boffo

paragraphs by Gary Provost over and over, and then trying something

similar. And failing--not

quite

miserably, but

badly enough that his imitations stand out like nipples through a wet

T-shirt.

But

back to Baffled,

a clever,

crafty, murder mystery, swiftly paced with memorable characters,

snappy dialogue, and believable suspense. It’s premised on the

suspicious death of Molly Collins, world-famous Boston advice

columnist, who was a dear friend of Jeff “Scotty” Scotland, the

aforementioned failed freelance writer. Scotty is convinced the

driver who ran Molly down on a Boston street did so deliberately. The

paper she worked for was being sold to a Rupert Murdoch-type,

profit-hungry tycoon with a reputation for buying reputable

newspapers and stripping them of their journalistic scruples. The new owner is running a national contest to pick Molly's successor. Scotty

believes this is somehow connected to her murder.

As

with Stephen Bogart’s two novels, real life has a way of poking its

head through the thin veneer of fiction. Bogart’s celebrated

parents and his own problems handling the celebrity they bequeathed

to him give his writing a cachet and voyeuristic allure of the sort

that can make publishers drool. Baffled

in Boston’s

backstory is less prominent. Its protagonist, of course, is a mirror

of its author. Provost, who

had been dead a year when the book came out. In retrospect it appears

Provost revealed, unwittingly one suspects, some prescience that

brings a sad note to an otherwise sweet romp of a mystery:

“I

was in Dr. Lewis’s office,” Scotty

tells us,

“because I had become terrified about my health. My heart seemed to

beat too often. My fingers trembled over the keyboard on my word

processor. And often I felt as if a load of laundry had been stuffed

into my chest cavity.”

This

brief biographical sketch appears on Provost’s Web page:

Before

the heart attack snatched him from the publishing world, Gary had

sold 22 (fiction and nonfiction) books to major publishing houses.

He’d been dubbed “The Dustin Hoffman of writing” for his

versatility, and he’d sold books in most every genre: How-To texts

for writers. True-Crime. YA novels. Satire. Mystery. Celebrity

Biography. Business. Sports. Romance. Cooking.

Anything writing-related, Gary

could do. He was an editor, book doctor, consultant to business,

ghost-writer. And, out of a field

of 12,000 applicants, he was one of only seven finalists in

the Chicago Sun-Times’ search to replace advice columnist, Ann

Landers.

|

| Gary Provost |

No comments:

Post a Comment