Dolphins,

Daytona, Glades, and Gators notwithstanding, Florida has never held

much attraction for me. Not sure why. Been down there a few times, to

the races, to visit friends. No bad memories—I actually kind of

liked the place. I've enjoyed reading about it—MacDonald, Hiaasen,

Holland

come

to mind—but when I'm not actually there I

feel

no chemistry, no pheromones

pulling me south. Not like Callifornia, which I visited once long ago

and still carry in my heart.

Maybe

it has something to do with my mother and the oranges. She complained

that Florida oranges were more acidic than California oranges. I

never noticed any difference, but I'm

learning more and more

Gert's influence went

deep. Not that I look at the labels. She didn't go that

deep. I can't help but wonder, tho, if maybe her orange bias didn't

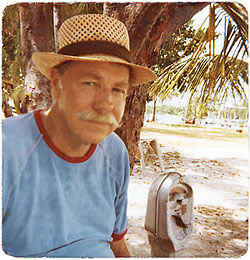

somehow affect my nonchalance toward Charles Willeford.

It's a stretch, I know, especially considering all of the positives.

Despite

enthusiastic endorsements from a couple of crime authors whose blogs

I followed—Ed Gorman and Bill Crider—I never had quite enuf itch

to read Willeford.

It took another crime author, Ben Boulden of

Gravetapping,

to lead

me into Willeford's world. Boulden

posted

a

link

on

Facebook that

took

me to the

gate,

a long Daily

Beast piece

on Willeford, with this headline:

The

Train-Hopping, Nazi-Fighting Literary Hero You’ve Never Heard Of.

Resist a pitch like that?

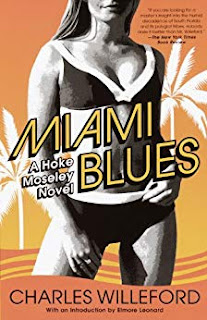

Hell, I read a few paragraphs and suddenly my fingers dashed off to the Kindle library and with no more thought than it takes to breathe downloaded Willeford's first novel, Miami

Blues,

which

is also the first in his four-book series featuring Detective Hoke

Moseley. I will read the rest, if my doctor allows me to do that much

laughing and experience that much suspense. I shook my apartment's

flimsy walls laughing at the opening scene, perhaps echoing

Willeford's own laughter when he described it to friends (see

Marshall Jon Fisher's

piece in The Atlantic

if you think I exaggerate). In fact, I'll let Fisher, whose parents

knew Willeford, describe it himself:

"I remember him roaring with laughter while telling my parents

about the opening scene of his novel-in-progress, which would become

Miami

Blues.

In it Freddy Frenger, a haiku-writing psychopath, brutally breaks the

finger of a Hare Krishna in the Miami airport. Frenger goes on his

merry way, and the Krishna collapses in shock--and dies."

Miami

Blues

doesn't have much of a plot, and it includes the kind of

coincidences critics sniff at writers for, calling the unrealistic

events deus

ex machina. Well,

bon

golly molly!

Willeford,

who won the Silver Star in WWII, gave a couple of nostrils full of

industrial grade ammonia to any critics who wished to sniff at the

big fat deus

ex machina he

stuck

right

in chapter one:

The

19-year-old hooker Freddy Frenger hooks up with at the hotel, where

he’s staying under a fake name is, unbeknownst to him, the dead

Hare Krishna’s sister.

And

Willeford follows this up with another, an even more outrageous deus

ex machina, giving

sniffing critics

a one-two punch combo (he did some boxing, too), when he brings

series star Moseley together with the doomed (we know) young couple

driving them to the morgue so the hooker can identify her brother. In

the car Moseley’s cop instincts immediately pick up that Frenger’s

hinky, but as he’s only investigating the Hare Krishna’s death he

merely files this away for possible future reference. Neither Moseley

nor Susie Waggoner, the hooker, know Frenger’s the one who broke

the finger. You must believe me that altho this sounds like a blazing

satire, Willeford delivers the humor so slyly, so nonchalantly,

you’re apt to ease along with it, laughing to yourself while

seriously hooked on wondering what the hell the next page will

reveal. I did, anyway.

One more laugh and then I’ll move along to something else. Susie’s an

inexperienced, barely competent hooker who came to Miami from

Okeechobee with her brother to abort the baby he’d impregnated her

with. They decided to stay in Miami—brother hustling Hare Krishna

at the airport, Susie hooking at the hotel, to earn enuf money to buy

a Burger King franchise. Frenger “rescues” Susie from her job and

takes her to another hotel. He tells her they’re married

“platonically,” which she seems to understand, altho what Frenger

really means is that they’re shacking up, which she accepts without

question. He’s the nicest man she’s ever known, she tells him,

and evidently means it.

While

Susie keeps house Frenger’s at the mall mugging drug dealers and

pickpockets, and Detective Moseley returns to his daily life, which

amounts to paying half his sergeant’s salary to his ex, and living

free in a Miami Beach fleabag hotel where he earns his keep doing

minimal security work. Things heat up when Frenger, who somehow gets

Moseley’s address, mugs him in his hotel room, beating him badly

and stealing his gun, his badge, and his blackjack.

Moseley

wakes up in a hospital with no idea who attacked him. The narrative

here becomes so realistic--focusing on the injuries, the treatments,

the hospital expenses, the problems his department has muting the

embarrassment of a cop losing his badge and gun, the fact that he’s

been living illegally out of his jurisdiction—that, even tho I

hadn’t thought I’d gotten to know Hoke much yet, I cared about

all of this, as if he were a friend or relative.

When

the narrative shifts to Frenger’s problems, his viewpoints, his

predicaments, I feel as as if he’s the brother who went bad, but is

still a brother. Willeford’s writing incrementally creeps into your

sensibility (mine, anyway), making it hard not to identify with which

ever viewpoint is at bat. And there are believable parallels—each

is even struggling to quit smoking. We know they’ll inevitably meet

again, and it won’t be friendly.

As

the showdown approaches, we’re in Moseley’s head, filled with the

need to avenge himself as well as bring a criminal to justice. He’s

ambivalent about the meeting. “The

more he thought about [Frenger], the more afraid he was,” he tells

himself. “This was not paranoia. When a man has beaten you badly

and you know that he can do it to you again, a wholesome fear is a

sign of intelligence...his only chance was to spot him in the street,

and that seemed damned unlikely. Deep down, way down there in the pit

of his stomach, he hoped he wouldn’t find him”

He’s

still musing when he finally does:

“Freddy

Frenger, Jr., AKA Ramon Mendez, had played out the game to the end

and didn’t really mind losing his life in a last-ditch attempt to

win. Junior would have been good at checkers or chess, thought Hoke,

where sometimes a poor player can beat a much better one if he is

aggressive and stays boldly on the attack. That was Junior, all

right, and if you turned your head away from the board for an

instant, to light a cigarette or to take a sip of coffee, he would

steal one of your pieces. Junior didn’t have to play by the rules,

but Hoke did.”

Well.

We know who won, else there wouldn’t be three more published Hoke

Moseley novels and another one available in

typescript available for reading only in the Charles Willeford

Archive at the Broward County Library.

Oh,

I must not omit the last laugh, on the last page, an item in The

Okeechobee Bi-Weekly News:

OCALA—Mrs.

Frank Mansfield, formerly Ms. Susan Waggoner, of Okeechobee, won the

Tri-County Bake-Off in Ocala yesterday with her vinegar pie entry.

The recipe for her winning entry is as follows:

I

thought it was a joke, as I’d never heard of nor could imagine

vinegar pie. I Googled it. It’s real, it’s Southern, and it sounds right tasty.The recipe's the last thing in the book!

I need to read more Willeford. Thanks for the reminder and the link to the article.

ReplyDeleteMy pleasure, Elgin. I intend to read more Willeford too!

Delete