The

advent of flash fiction has been a godsend for that part of me that

prefers the kill to chasing a quicksilver fox, the visceral

capture that eludes the academy poet.

At first thought one might

think short is simple and simple is easy, and this may be so for

some. Even many. But, as in most art forms, the occasional genius

brings surprise to the party. Brilliance that beacons through eons of

comfortable fog and expectation.

Such

is Alligators

at Night,

a collection of seventy-two quickies that pierce the heart and the

funnybone—sometimes within a word or two, sometimes in the title

alone. Meg Pokrass is celebrated among her flash-fiction peers for

her deft hand arousing glee in the darkness and sober reflection

before laughter’s quite finished its happy sputter.

“You have

not yet cried or threatened to leave,” we learn in the title story,

“and you have not yet been quieted by your husband with his body

half-asleep and given up the fight.”

But that

comes soon after the opening, when she explains the odd title, when

life seemed fine, its quirky behavior carrying a tender poignancy:

You remember when you lived in

Florida briefly, walking to the store with your husband in the middle

of the night. You remember the sound of alligators crooning like

deranged, nocturnal cows, all the way to the Seven-Eleven, from each

side of the highway. You remember thinking that they must regularly

sing to people on their way to the Seven-Eleven— mostly a welcome

sound, because there is a three-hour walk there, and a three hour

walk home, and the night sky is so velvety in the summer, and the

singing alligators are like jazz. It’s like you’re in a jazz

club, but walking, outside.

Funny

title? How about Dismount?

I guess that depends on connotation. Is the story funny? It gives

sequin flashes of mirth, but then this line:

“She

imagined heaven an aquamarine deep swimming pool where she could cry

underwater and nobody would know.”

The

instantaneous back and forth between twinkle and anguish

give Pokrass a dangerous edge, like a cat purring when its belly’s

scratched switching in a blink to jungle mode, all teeth and claws. A

lightness of style pulls us into a queenly Dorothy Parker mind where

nothing ameliorates the keenest and meanest of observations. Her

delivery is sly, indirect, and her cuts frequently self-inflict. In

Cutlery

she tells us her lover has an obsession with kitchen knives. “We

were each part of an intricate and delicate habitat, and we had our

own ways of surviving. He had his butter knives. I had my fantasies

of finding a man who would find me.” Ouch.

Her

wit is not all she displays in these jewels from a mind you sense

lets nothing get past, that once caught by her perception it’s a

permanent acquisition. These sparks of insight and wonder are grist

for the mill of an accomplished wordsmith, bubbling from a vast and

deep memory seemingly on a whim into carefully wrought, playful

sentences that showcase them with dazzle and shimmer. “He slices a

sleepy-bear smile my way,” she reveals in The

Landlord,

“and my mouth stretches sideways and upward like a circus trick.”

“Johan

is looking at me with a smile that stretches around his smile lines,”

we learn in Probably

I’ll

Marry You.

“He has a cute, rat-like face. Rats are very intelligent animals.”

Some

of you may be curious about length. Just how long are these “flash”

stories? Am I misleading you with fetching quotes? Luring you into a

collection of ponderous stories so long you have to break from

an engaging narrative to pee or get another beer or glass of wine,

and then be

distracted by something else, and when finally you get back to the

story you’ve forgotten what in hell it’s about? Would you like an

example of a typical story right here, right now? Can I give you one

without violating the copyright rigidities designed to protect author

and publisher from pirating? Well, dammit, I’m

no pirate, and

if Meg Pokrass can be daringly whimsical, so can I. Here’s an

entire story from the collection Alligators

at Night:

Man Against Nature

I stand near the boiling

stockpot warming my fingers while the chicken and vegetables melt,

the smell making our apartment strong. Canned wind howls from the TV

screen in the living room, emitting a cool glow. He loves

man-against-nature shows which are actually a buff-looking male model

talking to himself (and his hidden film crew) before lunch which is

probably catered sushi. I serve him the fresh broth on a lockable

tray, move his legs from couch to the floor, bend my knees to avoid

using my back. He drinks soup with a special deep spoon— and though

his fingers tremble, they are able to grasp. I sit with him, cheek

against his warm shoulder, watching the man trapped between two icy

mountain ranges build a fire out of sticks.

Do you

trust

me now? An entire story you just read in the time it took your heart

to beat, what, ten,

fifteen

times? Three or four natural breaths. Even if you had to pee like a

racehorse you could have made it through this amazing piece before

trotting off to the throne. And then

remembered

it when you got back. Irony?

O lort, I believe I failed to mention irony up above, but in this

piece alone, in Man

Against Nature,

there’s enough irony to put Olympic zip into the most anemic reader

(metaphorically speaking, of course). I don’t believe Pokrass can

write more than five or six words in sequence without slipping in an

ironic twist or three. And some of the other concepts de

rigueur

among the

popular

literati—subtext, layers, nuance,

resonance, MFA

approved, etc.

It’s all there. All of it, packaged in hot little bundles of

blinding

brilliance.

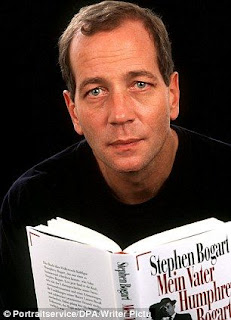

|

| Meg Pokrass |

What’s

that? You want another taste? A little encore of sorts? Well, I can’t

say I blame you. Okay, so here’s another line from Probably

I’ll Marry You:

“My

ex-husband was a workhorse, never lost a job. Kept his pants real

nice. Had a Grecian nose. The woman my husband left me for has a

piggish, squashed-in nose. I have two arms, and my nose is terrific.”

The

link at the bottom is to a collective blogging feature called

Friday’s

Forgotten Books.

I put the link there because this essay is my contribution for this

week. Alligators

at Night

is not

a forgotten book. It came out last year, but I’m including it as an

introduction to readers for whom flash fiction is so new a concept it

could easily be overlooked in favor of more traditional fiction

forms. I don’t want to have to come back here in ten years or so

and treat Alligators

at Night

as a bonafide forgotten book. Please don’t let that happen!