I took a

couple of days off after reading

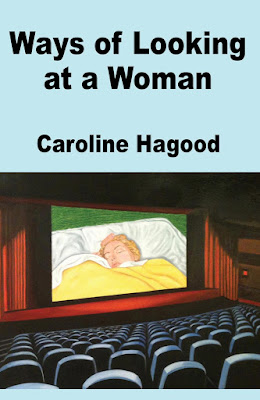

Ways

of Looking at a Woman

because I wanted the roiling, frolicking notions implanted by this

droll, ingenious look at writing, academics,

mothering, movies, womanhood, self-hood,

and

probably a few things I’m not remembering at the moment...I wanted

them, the notions, to sort themselves

out

unmolested so

I could see if the buoyant, sparkling mood this brief dance of poetic

prose put me in would last beyond violent interruption by the book

about an insane US president I had to read, and, if so, if it survived, to see

if a closer look might reveal just how

Caroline Hagood worked her literary

witchcraft.

My

Ways-induced

euphoria’s

intensity,

as I’d suspected, bullied me to cancel

the experiment for fear intentional

exposure to something notably

obnoxious

might

unfairly dilute

this sweetly

sensual spell.

It

became a struggle of willpower, which I won, possibly with the

serendipitous help from a silly ditty making the rounds on social

media. The lyrics parodied a popular tune for children:

If

you’re happy and you know it, overthink

If

you’re happy and you know it, overthink

If

you’re happy and you know it,

Give

your brain a chance to blow it

If

you’re happy and you know it, overthink

How

could it help, you wonder, when the

ditty was in-my-face

indicting

me,

a chronic worrier that happiness is a sham, simply

a

sly

subconscious

mechanism

for avoiding the ubiquitous signs of decay and

injustice and

suffering and

death and hideous executive

hairstyles. Well, it didn’t help. Not me. Not directly. Indirectly

it

did,

because as I knew its taunting, rhymy little message with its insipid

tune

insinuating itself into my brain as a damnable ear worm should have

deflated

the euphoria Hagood’s magic had

given

me, but

it

didn’t!

And

Hagood clearly was more vulnerable to overthinking than I am. In fact

overthinking is the wings

of

Ways:

extended angsty juggling of interplaying expectations, obstacles,

disappointments, writing failures,

academics,

mothering, movies, womanhood, self-hood,

and

those

other probable things I’m still trying to remember. Hagood

lays out the challenge with her first two paragraphs:

It

electrocutes me in the best possible way to watch the thoughts

marching from afar like a terrifying army.

What’s

this sick compulsion to shatter the celluloid that encases me, write

my way out with a lyric essay, pervade, project light through light,

wrap my head around what I am: a movie in the shape of a

woman, seeing and being seen, writer-mother, a mixed genre, a person

with another person growing inside her?

I

had to look twice to find the counterpoise among the negatives, the

“terrifying” and “sick compulsion” and “celluloid”

encasing her, but there it was: the incipient spirit that

graces not only the opening but the entire piece: a sense of

irrepressible ebullience, of joie

de vivre, of

wry, self-effacing

humor

that underlies virtually every thought, hell--every word

in Ways

of Looking at a Woman.

“It

electrocutes me in the best possible way,” she

says of the “army” of thoughts marching toward her to conquer her

happiness. She’s ready for them. Her hardy, drolly welcoming nature

beckons them to bring it on. And they do, and one helluva fight

ensues. And me, watching from the catbird seat, I’m gasping with

admiration, interspersed with honest laughter, taking notes like

crazy, all the way.

I

might have missed the whole show, tho, had I been a creature of

academia and discovered at the very beginning this woman’s doctoral

dissertation was quite the inept, fumbling,

disorganized, hootenanny ramble of scrambled notions daring to go

public before enduring the de

rigueur

gauntlet of peer and advisory reviews. Sacre

bleu!,

I might have ejaculated flinching at the “research proposal”

section's failure to conform strictly

to

the ivoried

rigors

of academic structure. These

reviewers would have withheld their horrified

gasps

reading the first two paragraphs, quoted

above, granting a brow-cocked pass on a presumed

cleverly

outré

lead-in to the

coherent,

no-nonsense

hypothesis with its

sufficient

data/citations and perhaps a preliminary pie or bar graph or two

before launching into the

deadly serious “abstract,”

with more of the same rendered more cautiously

and, most importantly of course, delivered in a timidly passive

voice. Here

is where I, were I the hypothetical bowel-constricted peruser, would have

blown into a bewildering profusion of dancing question marks, each

presenting a smirking little face forcing me upon my gown-muffled

oath, were I an 18th

century diplomaed pirate, to utter the dreaded ARRRRRRRRRRR

and hurl the blasphemous excuse for a dissertation as far and wide as

its unbound, coffee-stained leaves would carry it. Here precisely is

where it would have happened, when I read these very words:

“And

what will happen if I can’t? Will my skin curl, crack, and harden

till I’m mummified, bundled beetle-like in my own ambition? If only

someone had told me early on, ‘You will never get the orange peel

off in one clean spiral, but more haunting shapes will come out of it

in the end.’”

It

was here, still trying to imagine what new license had

been unleashed in the ivied walls of higher learning, that I glanced

at the table of contents and then scrolled quickly through the essay

to learn to my raucous amusement that Caroline Hagood was making fun

of traditional strictures, that her essay, which, while properly

peppered with sources and

hedged

arguments complete with big words, was really just a cap-and-gown

garbed poem about the inner and outer life of a brilliant, original,

contradicted, adventurous, questing poetic mind that paid no heed

whatever to its faux-architectural disguise. She leaps and

somersaults and backflips and handwalks her words down page after

page, ignoring such divisions as “methodology” and

“acknowledgments,” with its “introduction” in the middle, and its real acknowledgments in the “appendices” at the very

end.

Involuntary

giggles continue to diesel in my throat every time I recall Ways

to Look at a Woman’s send-up

of ivory-towered pomposity. And this, while knowing she’s busy

working on an actual doctoral dissertation, to which she refers with

gentle, respectful humor time and again.

The

only catiness I found in Ways

of Looking at a Woman

was directed at Norman Mailer, who, altho profoundly influencing my

outlook coming of age, I see now most definitely deserves the hisss

and scratch of Hagood’s claws in her book. I shan’t include any

quotes, as I’d hate to instigate a futile brouhaha here in the

relatively chaste cloister of my blog.

|

| Male Ego Personified |

I

said earlier I took a lot of notes. That was understatement. I copied

twenty-six pages of quotes from the book to my

offline review document. I cannot share many more with you, as the review then would risk straying into legal jeopardy as plagiarism.

Yet, I cannot pass up, for example, something like this:

“Mostly I didn’t write a memoir because nobody wants to read

something called The Subtle Art of Writing While Covertly Watching a

Zombie Movie, Playing Make-believe with a Tantrumming Kid, and Eating

Taquitos.”

Or

this:

“I

started wanting to use ‘I’

in the dissertation where it didn’t belong. On every page, Caroline

kept popping up—making lewd gestures behind a footnote, mooning me

from behind a piece of particularly dry text.”

I’m

gonna pound away at my computer to create the perfectly positioned

thought UFO to abduct my reader. – Caroline

Hagood, Ways of Looking at a Woman

Dear

Reader,

she

tells me, and only

me, I’ve

taken the liberty of imagining you as my soul mate, lover, best

friend, that person I’ve been looking for my whole life who will

make me feel less alone, understand my ravings, my UFO to nowhere.

The point is I see you. Consider yourself seen.” I

suppose this should be at the top in one of those full-disclosure

boxes disqualifying me as an objective reviewer. You can fool some of

the people...

|

| Meryl Streep? |

Anyone

so enticed by this thoroughly subjective rave they might wish to read

a real review should click here, on Pank

Magazine, for Dr.

Patricia Grisafi’s knowledgeable, academically sound look at Ways

of Looking at a Woman.

No comments:

Post a Comment