Weirdest

thriller I ever read. Slow, yet engrossing with well-paced suspense

and plausible action. Sort of a pop literary thing that avoids

pretension as well as the de

rigueur

cheap sizzle publishers assume the genre market craves. I chose it

for the promise of its title: Paris

in the Dark.

I spent some time in Paris long enough ago to feel the tug of

nostalgia for its uniquely familiar ambience—unique among all other

cities I’ve visited, its familiarity groomed

over

years of hearing and reading more about Paris than any other city I

knew of. Prompting me also to read Paris

in the Dark

was knowing it was set in the WWI years, a taste for which I’d

acquired recently from John Buchan’s wartime thrillers.

But...no

similarity between Buchan’s swashbuckling Richard Hannay and Robert

Olen Butler’s Christopher Marlowe “Kit” Cobb, a queer mix of

Hamlet, Ernest Hemingway, and James Bond. Another big difference,

which I didn’t discover until I checked the publishing date of

Paris

in the Dark.

Buchan wrote The

Thirty-Nine Steps

and Greenmantle

during

the WWI era, with its stereotypical characters and manic lingo. Paris

in the Dark

came out last year, giving it the advantage of a century of social

nuance that enriches the historical perspective with depth and

texture.

Kit

Cobb narrates Paris

in the Dark

so intimately we’re embedded in his head, privy to his every whim

and worry. I found this irritating at first, as the constant mulling

over what to do and how and when and where to do it seemed

unnecessarily meticulous, the to

be or not to be

soliloquy playing over and over and over. The irritation soon turned

to fascination, though, as I sensed the author’s invisible hand on

the controls moving the story deftly toward its inevitable

conclusion. Cobb, a credentialed news correspondent from Chicago, is

also a secret spy for an unnamed American government agency. Overtly,

he’s doing a story on the American volunteer ambulance drivers

based at a makeshift hospital in Paris. Meanwhile, working for his

spy boss, James Polk Trask, trying to identify, find, and kill the

saboteur who’s setting bombs off in public places. He and Trask are

working unofficially with the French secret service, which gives Cobb

the name and address of a German informant living in Paris.

|

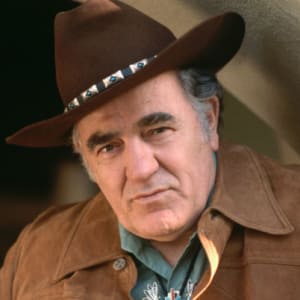

| Robert Olen Butler |

Cobb,

who speaks fluent German, learns from the informant of a German

assassin recently arrived in the city posing as a refugee. Cobb

locates the assassin in a German-run bar, and here we get a look at

Cobb’s struggle to manage the separate roles of his conflicting

identities as he makes friends with the refugee German bar patrons.

After buying a round of pricey imported Kulmbacher beer he begins to

feel a closeness with these patrons despite knowing he might have to

kill one of them. He creates in his head a German

word—Bindungsehnsucht--to

describe this closeness:

A

deep and complex longing for an emotional connection, for a bond. I

was surprised to think of this. I was here as a spy. One of them—

if he was not here at the moment, he could well have been— one of

them that they would hide and even assist could be a killer of

civilians in the name of war. The men in this room were the Huns. And

the connection they were creating between us was built upon my lies.

But

superficial lies. Lies that could easily have been replaced by

equally superficial truths. So easily as to show how irrelevant lies

or truth were to the making of this bond they sought. Because the

biggest surprise of all was that I was feeling the Bindungsehnsucht

in me as well. That they were Germans and I was an American or even

that I was an American spy portraying an American German to help

prosecute a war against them:

all that seemed somehow irrelevant. In this moment we were simply

men. In a bar. Finding things to bind us, to give us cause to shake

hands, lift our glasses, drink in concert, prop each other up, get

varying degrees of drunk together, come to a rapport. That the

rapport could be achieved over trivial and interchangeable things

only spoke to how deep was the longing itself and, therefore,

paradoxically, how profound was the rapport.

Of

course he has a fling with the head nurse at the American hospital,

and has to balance his conflicting roles for her sake, as well. But

this is a thriller, so things are not always what they seem. Cobb

finds the bomber—two of them, in fact—and, despite his

claustrophobia from having been locked in a Vaudevillian trunk as a

child, climbs down into the famous, skeleton-crammed Paris Catacombs

where he believes the two terrorists have gone to plant a bomb under

the site of a critical meeting between the French president and top

military leaders of England and France. The chase is on, in the dark

amid grinning skulls and scuttling rats. Cobb figures the bomb has a

ten-minute fuse. He hears the terrorists up ahead...

As

an example of Pulitzer-winning Butler’s mastery of his craft, the

following little scene sticks in my imagination more memorably than

the entire Catacomb chase. Cobb and Trask are sitting in a cafe

intensely trying to come up with a plan to catch the bombers:

“I

thought to simply drink my beer,” Cobb tells us, “and was

surprised to see it hanging in the air before me. I’d lifted it

along the way but I couldn’t recall when.

“I

put it down.”

Pretty

sure these guys were

not

doing

recreational drugs.