It takes me

a lot longer to read a collection of good short stories than it does

a good novel of the same length—even if the chapters are longer

than each of the stories. With chapters I can come back after a

break, and the story's still in my head. I might be surprised by what

happens in the new chapter, but, unless the novel is reaching for

literary cachet, the characters and the voice and narrative thread

are still the same. Not ordinarily so with individual stories.

Despite the ominous aura hovering over the pages of Monkey

Justice,

Patricia Abbott's twenty-three tales of people treading in moral

shadows, each story took me to a different place, with new

characters, different narrators, and no sure expectation of where we

were going.

This can be

a problem for me with fiction, as I tend to identify with the most

prominent characters. Whether I like them or find them repugnant.

Although occasionally in these kinds of stories—known as noir

in the milieu—I find myself caught up in a character who ends

badly, most of them manage to elude the disaster that another

character deserves, and gets. Abbott’s sorcery keeps me in suspense

this way, masterfully misdirecting right up to the surprise twist

that can come anywhere in the narrative. So even though I have a

general notion of what I’m getting into, Abbott pulls the rug out

from under me more times than not. Each story is like a different

Whitman’s Sampler chocolate without the guide. Is the round one the

good one, the caramel? Oops, nope, that’s the cherry

cordial...ptui.

Monkey

Justice

has all of the different shapes, but not a one is a ptui.

Do I have a favorite? This has yet to be determined. The swiftness of

a short-story experience can continue to play out in a reader’s

sensibility long after the reading. The

subtler ones take longer as various

nagging

nuances

refuse

to desist. Stories that give me the most trouble this way usually

feature a character who gives off hints of

being a little too close to the dark side.

I call these characters

“Lucifers,” although the best ones are too ambiguous for me to be

certain. Characters like Flannery O’Connor’s “Misfit,” James

Lee Burke’s “Legion,” or Walker Percy’s “Art Immelmann.” They have enough charm to keep me unsure if they are truly

Mephistophelean.

Are they just plain bad or is there something deeper,

something...well, other? They often have an odd odor and a knack for

insinuating themselves into my trust. They pop up when least expected

and coincidentally most convenient for

them.

I won’t

spoil your surprise by giving you the title of the Monkey

Justice story

from

which

Abbott’s

Lucifer character keeps

popping into my head, making me wonder if it

(no gender hint) is in fact an evil entity or

so

much like real people I’ve known that I shiver at the remembrance.

Another

story that lingers, this one continuing to arouse giddy chortles in my throat, also

features a sinister character. But this one I’ll not only share the

gender but the name, albeit Abbott gives her a fig leaf of anonymity

while ensuring we’d not mistake this former New York Times book

reviewer as anyone other than the woman Norman Mailer publicly dissed

in

a Rolling Stone interview as a “one-woman kamikaze,” and by Susan

Sonntag, who said, “Her criticisms of my books are stupid and

shallow and not to the point.” Abbott tugs the fig leaf back for a

flash of identity when she assigns to her “fictional” reviewer a

quote delivered by the living, breathing Michiko Kakutani in a review

dissing Jonathan Franzen’s memoir The

Discomfort Zone

as “An odious self-portrait of the artist as a young jackass,”

whereupon Franzen shot back with the ultra literary equivalent of yo

mama, calling

Kakutani:

“the stupidest person in New York City.” Oy

veh

(Oibikuru

in Japanese).

In Abbott’s

story the fig-leafed Kakutani is

called Madam X, and it’s told by a

former

gangland bodyguard now fallen to guarding spoiled celebrities. “She

told me stories about getting egged by a guy who wrote books about

bears,” he tells us, and I can feel his sneer. “Another melee

happened with a female writer dressed like a chambermaid. She’d let

herself into Madame X’s room in a Boston hotel, and hidden under

her bed...”

The story

ends with a twist, of course, making me laugh. And I still have no

use for Jonathan Franzen!

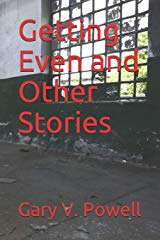

These are

only two of the twenty-three. I shan’t mention any of the titles,

for fear of giving something away that might spoil any of the myriad

gotcha

moments

sprinkled throughout Monkey

Justice.

Well, you can have one:

Monkey Justice, which also gives the book its title. In an interview,

Abbott attributes inspiration for the story to an incident on a bus

ride in Detroit. She overheard a fellow passenger telling a story to

someone else:

Who

could resist using a story about a man's wife and mistress giving

birth to his daughters on the same day? The guy on the bus becomes

Gene, the beta male, in my story. I even watched him de-bus at the

[Michigan] Science Center.

He will never know that his story became my story and the title of this collection.

He will never know that his story became my story and the title of this collection.

Abbott is

the author of the Anthony and Macavity-nominated novel Concrete

Angel,

the Edgar and Anthony-nominated Shot

in Detroit

and 2018’ s story collection I

Bring Sorrow and Other Stories of Transgression.

She won a Derringer for her flash fiction story “My Hero.” The

author of nearly 200 stories, she lives in Detroit. You can find her

on pattinase.blogspot.com.