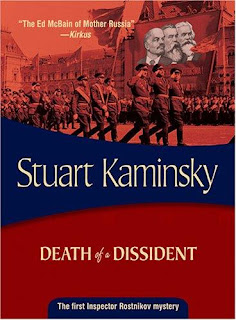

My initial brainstorm was to

copy Stuart Kaminsky's complete introduction to the Mysterious Press

edition of his Death

of a Dissident

with maybe a highlight here and there and an occasional comment of my

own to break it up. But I quickly realized copyright restrictions

would undoubtedly toss a greasy wrench into the plan, so I knew I'd

have to get off my lazy metaphoric butt and write an actual review.

Rest assured, however, Kaminsky's introduction is so good I still

intend to use great chunks of it, either in paraphrase or as direct

quotes. It's (as I would argue to the judge in a copyright

infringement lawsuit) unavoidable!

For one, Kaminsky relieved some of

my reluctance to read his crime novel about a Moscow cop, concerned

that maybe he wouldn't measure up well with Martin Cruz Smith's

Arkady Renko. I'd just finished re-reading the Renko

series

and enjoying it even more than I had the first go-round. Kaminsky

addresses that concern head-on. By coincidence, Death

of a Dissident came

out about a month after Gorky

Park, the

first Renko episode.

"Though I had

enjoyed Martin Cruz Smith’s novels— and still do," Kaminsky

tells us, "I couldn’t read Gorky

Park. The reviews

made it clear that

our

books bore only a superficial resemblance to each other."

I agree. Neither the plots nor

the styles are comparable much beyond their Soviet Russian milieu.

The Arkady Renko novels remind me more of the complex stories and

characterizations John le Carré

employs in his novels, whereas Death

of a Dissident

has an Ed McBain feel,

à

la his

87th

Precinct crime series. Oh, alright, I cheated on that one. Kaminsky

makes the McBain resemblance abundantly clear in his aforementioned

intro:

“I love Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct novels,” he says, and

mentions specific McBain influences throughout. But wait. “I also

love Georges Simenon’s Maigret novels, and John Creasy’s Gideon

novels were favorites of mine in high school. Above all, I love

‘classical’ Russian literature, particularly Dostoevsky and, even

more specifically, Crime

and Punishment.

And they

all, as well as Russian writers Chekhov and Gogol, come into play in

Death

of a Dissident.

His lead character, Chief

Inspector Porfiry Rostnikov, he frankly admits, “bears more than a

passing resemblance to Jules Maigret. His methods are similar, but

his milieu is much different. Rostnikov is, like George Gideon, a man

of action. And it is no coincidence that Porfiry Petrovich Rostnikov

bears the name of the magistrate who drives [Dostoevsky’s]

Raskolnikov to a confession of murder. Rostnikov, finally is my

fantasy of my Russian grandfather, my father’s father, who died

when I was about six.”

|

| Stuart Kaminsky |

Another

ensemble character, one of Rostnikov’s assistants in Death

of a Dissident,

he tells us, has a quasi-role model from the Star Trek TV series.

“Emil Karpo...is a tall, gaunt, loyal, humorless traditionalist who

bears some resemblance to Mr...Spock. Karpo is a haunted man who had

devoted his life and loyalty to the religion of Communism which, as

practiced in the Soviet Union, keeps letting him down. Karpo wished

to deny his emotions, the needs of his body and the human loyalties

which, ultimately, are more immediate than his devotion to duty.”

Rostnikov’s other assistant,

Sasha Tkach (no help with the pronunciation) is, in some ways, what

Burt Kling might have become in the 87th Precinct novels, had life

not dealt him a monstrous love life and had he been plunked down in

contemporary Russia rather than in Isola. Sasha’s concerns are

domestic. Life, the complications of a changing Russia, a growing

family, and his inability to cope with women threaten to overwhelm

him.”

So there you have the three

lead characters, explained in a way I suspect most English

teachers—high school presumably and most certainly undergraduate if

we’re talking college—would accept as analyses in a homework

composition or surprise quiz. And there’s even more in Kaminsky’s

intro for the serious pseudo-scholastic plagiarist.

As

for the plot, it’s classic McBain/Simenon/Creasy police procedural.

A famous Soviet dissident is murdered with a sickle in his apartment

a day before his scheduled trial, despite being under constant KGB

surveillance. Hmmm. The Soviets appear to be torn between rejoicing

and fearful the dissident’s death will reflect badly on them in the

West, as though due process was denied. So Rostnikov and his

sidekicks are encouraged to find the murderer so it appears justice

has been done. Any murderer will suffice so long as the government

can claim deniability. Rostnikov answers to the Cbief Procurator in

his precinct (or district or whatever the hell the Moscow political

division is called) is a good party member, but respects Rostnikov,

who is a good cop, and superficially a good party member. They get

along, unlike Renko and his bosses (called “prosecutors” in those

novels), where barely concealed corruption makes a mockery of party

ideals with every blink of every eye.

The

police work is credible and interestingly revealed, providing

opportunities to develop the characters in both their official and

domestic roles. Investigation is methodical, and when the routine

seems to be getting a tad tedious, some plausible action occurs to

break up the pace. One irritant broke up the mood for me, disrupting

my identification with the lead characters:

changing points of view. It’s one of the things I don’t like

about McBain’s novels. Too many heads to be inside, especially if

they’re villains. I did get to like the three main cops and their

procurator, a devout, workaholic Communist woman with an ailing

heart.

Thinking

the series was going to end after a

second outing,

Kaminsky says he considered killing off Karpo, the Spock character.

“In the first of several drafts of Black

Knight in Red Square,

Emil Karpo is killed. My editor and agent liked the character so much

that they persuaded me to let him live.” He notes that McBain

considered killing Steve Carella, his central character at the start

of the 87th

Precinct series. Fortunately for both series, the authors changed

their minds.

Kaminsky

tells of the trouble he had getting his Porfiry Rostnikov series off

the ground at all. “I liked what I had done.

My

agent liked what I had done. However, no hardcover publisher liked

what had been done so the book came out as a paperback original.

Death

of a Dissident

was submitted to the publisher and accepted almost a year before it

was published. [It]

suffered

the fate of most paperback originals:

no reviews.” Well, here’s one—better late than never, no?

Before

his death in 2009, he’d published fifteen more Rostnikov novels,

several other crime series, short stories and non-fiction works. His

fifth Rostnikov novel, A

Cold Red Sunrise

received the 1989 Edgar

Award

for Best Novel.

Mathew, I did not know that there was an introduction by Kaminsky in the Mysterious Press Kindle edition. Now I will have to buy that edition too. I only have the paperback edition. And this review also makes me want to read more of the McBain series also. I have only read the first four in that series. This is a wonderful review, I learned a lot from it.

ReplyDeleteThanks much, Tracy. I plan on reading more of the Rostnikov series, too. Thanks for the introduction!

Delete