Because of

neighbors who've

become hypersensitized to my sonorous emoting while engrossed in

crime novels, I nearly choked trying to stifle cheers when Geoffrey

Freeman dies a slow, extremely agonizing death. But it was Sunday and

my nearest neighbors—the next-door beauty parlor folks—were not

in, so my yays disturbed no one enough to bang on the pasteboard-thin

partition or call 911.

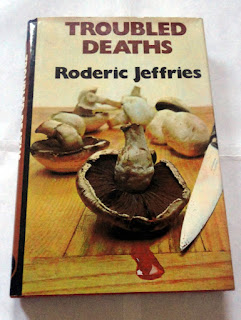

But then,

as it so often seems, complications appear. The chief suspect,

homely, awkward spinster Mabel Cannon, whose affections for Geoffrey

had been cruelly spurned, soon thereafter also dies a slow, extremely

agonizing death. Autopsies

indicate the two had been poisoned by a lethal mushroom known as

llargsomi,

which closely resembles the delectably edible esclatasang.

They grow wild in proximity to one another on Spain’s Balearic

island of Mallorca, but no Mallorquin would ever mistake the one for

the other—or so all likely suspects assure Inspector Enrique

Alvarez, himself a Mallorquin, assigned to investigate the presumed

murders of the two transplanted English residents.

Whereas the

pulse of other fictional detectives predictably would quicken as a

plot such as this thickens, Geoffrey’s autopsy, disproving the

initial theory he’d died of cholera, drives Alvarez to drink. The

game afoot for him leads straight to the nearest cafe for a brandy or

three. And the brandies continue as each Mallorquin he questions

welcomes him with spirits and bonhomie, and more spirits. Neither he

nor any of those he interviews expresses any love for the

English. “I’ll tell you one thing,” he confides over a glass of

brandy to Ramez, his cousin’s husband, “if I had the chance I’d

bump off all the English for nothing.”

The only

fictional police detective I know of whose drinking legs are in

league with

Alvarez’s

is Arkady

Renko,

Martin Cruz Smith’s vodka-swilling Moscow cop who at least has an

excuse, being beaten, frozen, irradiated, stabbed, and shot in the

line of duty. Obese and physically unfit to play any TV cop other

than Chief Ironside, Alvarez does catch some verbal abuse, but it’s

from his superior, a Spaniard from Madrid, who first orders Alvarez

to root out and destroy all llargsomi on the island, then, when told

how impossible that would be, orders him to arrest somebody—anybody,

it would seem. “That popinjay!” Alvarez’s cousin tells him.

“What does he know about anything? If he isn’t satisfied with the

way things are done on this island, why doesn’t he go back to

Madrid?”

For all

that, even though Alvarez does solve the murders, he hasn’t made

any

arrests in the three books of the series I’ve read thus far.

Mallorquin justice, perhaps, or Roderic Jeffries’s clever

plotting...or maybe the boss from Madrid has a point.

|

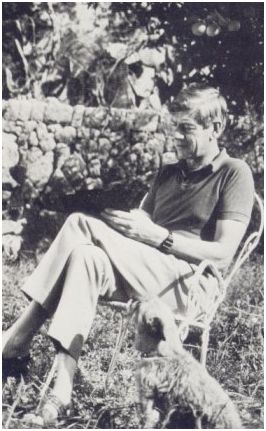

| Roderic Jeffries |

One thing

is beyond speculation:

Alvarez

is an almost hopeless romantic. We learn more in Troubled

Deaths

about Juana-Maria, the love of his life he lost in an as yet

unexplained fatal encounter with a motor vehicle. We’ve gotten

incremental bits of the story in each episode, just enough to lure

one further into the series. His fantasy surrogate Juana-Maria in

this story is poor Mabel Cannon’s only friend, Caroline Durrel,

whom Alvarez presumably would exempt from his

bumping-off-Mallorca’s-English-inhabitants fantasy.

“It

wasn’t her looks, thought Alvarez with bewilderment, although she

was as beautiful as an orange grove at blossom time. It wasn’t that

she promised that ripe, earthy experience which twisted a man’s

soul–she didn’t. It was because there was an air of simple

goodness about her which reminded him with aching intensity of

Juana-Maria.”

Not that

Alvarez turned up his nose--“broad enough to make a landing space

for a squadron of flies”--at the idea of earthy experience. He

muses that “these days most young women whether standing or walking

struck him as erotic...The tragedy

of middle age

was that a man still dreamed, but the volcano in his belly had died

down to just a little camp fire.”

Staring

into a bar mirror at one of his ubiquitous haunts, he sees “a

middle-aged man with lined, coarsely featured face, whose eyes were

bloodshot and whose hair was beginning to thin. You simple fool, he

[says] to his reflection. You, a failure, a peasant without a single

cuarterada of land to call his own, old enough to be her father...But

her

golden image continued

to dance in his mind...When he had looked at her he had seen the

quiet moon in the star-studded sky, the sparkling of still seas, the

distant mountains framed against a sunset sky. And when she had

looked at him, what had she seen? An

ugly, time-scarred peasant.”

A man who

knows his limitations, as Harry Callahan, another fictional cop once

said, but, as yet another, Colombo, knew, who uses humility to his

advantage. When he comes upon an English murder suspect in Caroline’s

company, the suspect insults Alvarez, presuming the detective doesn’t

speak English. I easily imagined Peter Falk’s New

York

accent and humble dissembling in the Mallorquin’s response:

“ ‘I speak a very little, señor, but that little not very well,’

said Alvarez, with the self-deprecating politeness which in Spain

sometimes took the place of rudeness. ‘I fear I make many

mistakes.’ ”

Caroline comes to his rescue.

“ ‘Well,’ she says, ‘it sounds to me as if you speak it

wonderfully well...I only wish I could speak Spanish half as well.’

Her eyes were deep blue where Juana-Maria’s had been dark brown,

yet to look into them was to look at what had lain in Juana-Maria’s.”

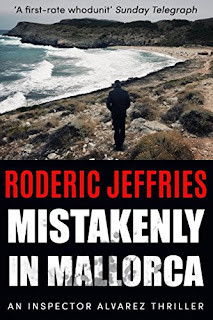

It’s a long series,

friends--some three dozen episodes, and not all are on Kindle. Woe is

the curious romantic in me.