I will

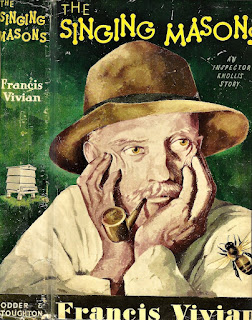

remember the stuff about bees in The

Singing Masons

long after I've forgotten the plot and the human characters and the

name of the author. This is not to say the murder mystery and the

people and the writing were merely so-so. All were top-notch (to my

admittedly less-than-sophisticated taste). The

bees play a marquee role, and

yet they’d not have had

the chance to

steal the show were it not for the honey trap promise

of

an intriguing human crime mystery. Were

the book only about bees

I doubtless never would know that half of

them

buzz off with a newly hatched queen to start a new colony, leaving

the old gal to rule the half that stay behind with her in the

original hive. It’s what they do.

It helps my

suspension of disbelief in this work of fiction that a copy of The

Singing Masons

resides at Cornell University in “one of the largest and most

complete apiculture libraries in the world,” and that Vivian was

himself a dedicated beekeeper. This I learned also in the book’s

Dean Street Press edition from its introduction by crime fiction

historian Curtis Evans.

Vivian,

born Arthur Ernest Ashley, was writing for newspapers and magazines

when he began cranking out novels in 1937. Published in 1950, Singing

Masons

is the sixth of ten in a series featuring Scotland Yard Inspector

Gordon Knollis. In Singing

Masons,

Knollis is brought in to assist Clevely

Borough Inspector Wilson investigating the discovery of a month-long

missing local lothario in an abandoned well hidden under a beehive.

The list of suspects in this small community is not long:

the victim’s fiancé,

whom he had ditched a day before he disappeared, her lawyer father, a

couple of his married sexual conquests, including a cousin who has

slapped him publicly only days before he disappeared, and her

husband. The usual motives are in play, including blackmail, money,

and scandal—intertwined and separately. Thoroughly unlikable, he

was, except evidently to certain women. The kind of jerk I just might

have pushed alive into the well myself, especially knowing he had a

cardboard container of calcium cyanide in his pocket that would

release lethal gas when activated by water. Cyanide, I can note

without spoiling any plot twists, he’d been planning to use on one

of the suspects! Had I done so—pushed the blackguard into the

well—presumably without the proverbial airtight alibi, local

Inspector Wilson could easily have solved the mystery all by himself,

as I would not have had the pluck to cover the well with an empty

beehive. Then again, everyone except those who didn’t know bees

knew the property’s recently deceased owner loathed bees.

Ah,

“The bees! The bees!” as Nicolas Cage wailed in The

Wicker Man.

Singing masons, as Shakespeare called them in Henry

V:

For so work the honey-bees.

Creatures that, by a rule in nature, teach the act of order to a

peopled kingdom. They have a king, and officers of sorts. Where some,

like magistrates, correct at home, others, like merchants, venture

trade abroad. Others, like soldiers, armed in their stings, make boot

upon the summer’s velvet buds, which pillage they with merry march

bring home to the tent-royal of their emperor, who, busied in his

majesty, surveys the singing masons building roofs of gold. The civil

citizens kneading up the honey. the poor mechanic porters crowding in

their heavy burdens at his narrow gate. The sad-eyed justice with his

surly hum delivering o’er to executors pale the lazy yawning drone.

Old Heatherington, the local

bee guru, offers a more vivid, if less poetic description. Watching

the bees at one of his hives reminds him, he tells us, “of a group

of village women preparing for an annual outing from the chapel. Some

trotted from the interior of the hive, seemed to chat with other

bees, and hurried back indoors as if they’d forgotten something, or

had a message to leave.

“Others

wiped their faces as if dabbing a final touch of powder on a shiny

spot. Others took off to circumnavigate the hive and land again with

weather reports. All were waiting for the signal to leave their home

and go out into the world to found a new colony, obeying the primal

order that all living things shall endure, shall multiply, and

endeavor to cover the earth.”

To

me that is the greater mystery, of much more fascination than who

killed the village cad and why. Puzzles can be fun for a little

while, diverting the mind from the predictable of diurnal duties. But

I’m retired from the harness, and my attention now wanders freely

from frivolous precisions. I simply don’t care whether an alibi

crumbles because the Sussex Bank clock said nine-oh-five when the

suspect insists it said nine-thirty, or when the TV show he/she

claims to have been watching when the dastardly deed was performed

had been pre-empted by a public service announcement from Ten Downing

Street. Or maybe I do care, a little, but let it slip past me in a

narrative that distracts my eye like a sleighting hand hidng a card

trick. And I do notice the obvious tricks, but feel cheated when it

becomes obvious I was supposed

to see the obvious trick that really has no bearing on the case. I

possess the patience level of the jigsaw puzzle solver who snips a

corner off an infuriating piece or hammers it with his fist to make

it fit in the damnable space where it should but doesn’t belong.

Mystery novels can do that to me. At some point I tire of the

detecting, and just want to see some schmuck I’ve sort of suspected

all along get what’s coming to him. Or her.

With Inspector Knollis, tho, I

rather enjoyed watching him check this and check that, say this and

that and some more of this as he worries himself and poor Inspector

Wilson half to death inching his way incrementally toward the wrong

suspect, until…

Here’s

a fine example of what I’m trying to say, his theory of detection:

“The facts of a murder case are like the lines of a poem or

song—they make sense only if you get them in the right order.”

And

this:

“It was seldom Gordon Knollis evolved a theory early in the course

of an investigation. His method was to seek a pattern in the events

surrounding the murder, a pattern which suggested, if no more, the

causal factors, and a pattern in which the murder was the focal

point.

“The

murder itself, despite its sensational nature, was not the vital

factor in a case as Knollis saw it; rather was it the bubble in a

swamp telling of long-repressed forces beneath the surface, the

eruption telling of poisons circulating through the apparently

healthy system, the molehill indicating the runs and tunnels hidden

from the eye.”

In this case one might add,

follow the bees.

[For

more Friday's Forgotten Books check the links on Patti

Abbott's unforgettable blog]

No comments:

Post a Comment