Take, for example one of the

owners of George Bellairs's fictional antique shop, a man referred

to only as "Mr. Small" but described in grotesquely comic

detail as "an enormous man

with a huge paunch which hung between his knees when he was sitting.

He had solid limbs like the branches of an old tree and a round

florid face. His head was shaped like an orange and topped by a

brown, ill-fitting wig. His thick, sloppy lips, large Roman nose,

small shifty eyes and ill-fitting clothes finished-off an appearance

more like that of a shady broker’s man than an expert in old

furniture and prints...so

flabbily fat that he looked to be trundling his paunch before him

like a railway-porter wheeling baggage about...He was smoking a black

cheroot which he kept removing from his mouth and then replacing with

a repulsive movement of his lips, like a hungry child taking the teat

of a feeding-bottle."

Bellairs describes Mr. Small’s

niece, Mrs. Doakes, who worked in the shop with her uncle and his

brother-in-law, tiny Mr. Grossman, as “a

tall, muscular, good-looking woman” with

“a way of exciting men whilst putting women out of countenance.

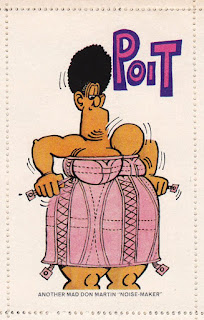

Martin might have depicted her thusly, with some essential

tweaks:

The entire crew of this novel

are portrayed so comically I nearly forgot I was reading a murder

mystery, with two violent deaths—one so ghastly I had to wonder if

Edgar Allen Poe had gotten a hand in it somehow. Tiny Mr. Grossman is

the first victim, found curled up, suffocated, in an antique wooden

chest he’d bought from a woman who eventually becomes the second

victim, found with her head crushed by either an assailant or rocks

at the foot of a cliff from which she’d either jumped or been

hurled by a murderer. Tough, I should think, for Don Martin to win

laughs with a drawing of that. Perhaps Gahan Wilson could have been

brought in for the victim illustrations were time travel an option.

It’s a well-crafted mystery

with enough plausible suspects to challenge even the most astute

puzzle-solvers, albeit a distinct gullibility in such exercises can

challenge my opinion. Anyway, this one fooled me right up to the

reveal’s edge. I’m not too proud to blame the thrall holding me

captive by Bellairs’s characters. Like a magician’s distracting

hands, their general comic weirdness consistently diverted my

attention from the story’s Sherlockian signposts. Oh, where to

begin?

|

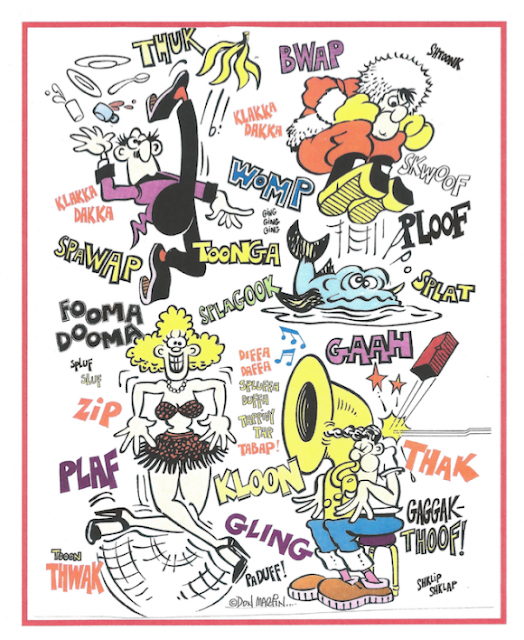

| Don Martin |

Miss Selina

Adlestrop, a spinster whose

“small button nose, like a

whiteheart cherry, little heart-shaped lips and a timid, faltering

manner...stood her in very good stead and hid her shrewdness in

striking a bargain,” which

she employed whilst haggling over the chest-cum-coffin with the tiny

Mr. Grossman, whose small

hands and feet and slim figure and “grace

of movement of a ballet dancer”

attempted to charm from her

more quid than she’d have

preferred to put out for the item so dear to her romantic heart.

Then

there’s the local constable, Donald

Puddiphatt, a duffer

“perspiring from every

pore and puffing like a traction engine as he argued with Seth Hale,”

the local undertaker. “They were an ill-assorted couple. One looked

to have been poured into his uniform which fitted him skin-tight

owing to his ever increasing size; the other was nearly as fleshless

as a skeleton with old clothes hanging from his bony body like

washing on a clothes horse.

A great brouhaha breaks out

when the chest is opened in Miss Adlestrop’s rooming house, and

Grossman’s little body is discovered curled up inside. Women

faint. One becomes hysterical and has her face slapped by another,

and Seth Hale, the skinny undertaker, “fell unconscious to the

ground with a great rattle of bones.”

Oh,

and there was the local politician, Councillor

Blanket, who “ looked

made-up for the part of John Bull, like an actor just ready for the

footlights. Grease-painty complexion, tufts of hair, bald head with

puffs of white at the side,” and

Miss Adlestrop’s uncle, Mr. Alfred, a “rabbity”

little eccentric inventor

“with a squint and a

ragged moustache,” who,

"ran so fast from the pandemonium you

couldn’t see his legs going, like a mouse," with

Councillor

Blanket in tow, “lumping

along steadily, his head held firmly erect to keep his hat from

falling off.”

Superintendent

Gillespie, in

charge of the investigation for the local constabulary,

“would go for days without speaking to anyone and then suddenly

change into bouts of great jocularity.He always wore his hat in the

office when his liver was wrong side out. He said there was a draught

from the windows, even when they were closed.” It

quickly became clear the case was too much for Gillespie’s force,

so his boss, Chief Constable Colonel

Carslake, “tall, thin, peppery and self-important,” was forced to

call in help from Scotland Yard, hence the arrive of

Detective-Inspector Littlejohn,

of the Metropolitan C.I.D. A one-man cavalry, who, for some odd

reason is not described in any way, presumably because he’s the

only character in the novel who doesn’t look or act funny, and

Bellairs was relying on reverse imagination to suggest ordinary

sanity and appearance.

The

coroner, Emmanuel Querk,

tall and

thin with

“a peculiar head...only a little broader than his long neck,”

ending

in a point from which “a fringe of downy grey hair spread like a

curtain over his neck and ears.” A

man of multiple quirks, including an aversion to noise, Querk rushed

through his inquest into the murder, adjourning it soon after

a “hurdy-gurdy started in the street outside just as he was

directing the jury and he could hardly wait for their verdict and

beating a hasty retreat to his private room. There he locked the

door, unlocked a cupboard and took out a bottle of whiskey.

It was all that stood between him and the complete madness to which

his wife’s endless debts and incessant nagging were driving him.”

Even

Bellairs tires of the inquest, giving us a break from monotonous

testimony because “we have

heard it all before and it would be sheer

torture to go over it again in the form of Puddiphatt’s official

statement.”

Bellairs

evidently has a thing for tweaking clerical noses. In Intruder

in the Dark,

the first of the Detective-Inspector Littlejohn series I’ve read,

he makes fun of the vicar’s “fruity voice.” In Seven

Whistlers, the

Rev. Mellodew Gryper has “a

voice like an oboe” and is

shown Ichabod Crane-like at a funeral in which “the

mourners had to struggle to keep themselves upright against the stiff

breeze blowing from the sea. The parson’s vestments flapped at

right-angles to his body. The bearers staggered beneath their burden

and tottered from side to side as they advanced to the graveside.

Tall, tortured trees surrounded the churchyard, leaning at an angle

caused by the fury of the prevailing winds.”

In another scene, conducting

sack races for children in a local festival, his oboe voice is grist

for sniggering: “‘Oh, what a shame, Bertha. On, on, you’re

winning. Ohhhhh,’ he oboed, trying to urge them all on without fear

or favour. He sounded at times as though somebody were murdering him,

and his contortions suggested that someone might have dropped a

wasps’ nest down his pants.”

|

| George Robey |

One last ridiculous character

of the many who tortured my funnybone as I vaguely wondered which one

of them might not have been the villain who locked poor itsy bitsy

dancing Grossman in the chest and left him to suffocate, essentially

buried alive. I give you the insignificant-seeming Mr. Troyte, in a

walk-on, walk-off role (perhaps exiting in handcuffs, making wuffing

noises as he goes?): “a

small, portly man who looked like a pug dog with George Robey

eyebrows...

Yeah, I enjoyed this book as well. I don't think I've ever laughed so hard upon the discovery of a dead body as I did at poor Mr. Grossman's ghastly tea party appearance. SO funny. So right on the money. In truth the book is worth reading just for this scene alone. Great review, Matthew.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Yvette, and thanks for introducing me to Bellairs!

DeleteWell, Matt, unfortunately I chose to not host the joke about the spammer you posted to the FFB post, since it could be taken by the literal-minded or those choosing to insist as a genuine threat, which a prick such as our spammer could use as an excuse to get Blogger to kill the blog, as opposed to the nothing which will get Blogger to address that our spammer or spammers are using their blogless Blogger accounts to facilitate spamming.

ReplyDeleteGood point, Todd. Hadn't thought of that. It's why the security curating feature is a necessary distraction. But I'll say this on my blog, spammers should be soundly flogged and introduced to the fire-ant community in Florida.

DeleteI did a little bit of looking for online copies of George Bellairs' books, and it looks like I will have to settle for some ebook editions, except of course for the few that have come out in the British Library reprints. Oh well.

ReplyDeleteI've stopped buying paperbacks except for the occasional gift, Tracy. I'm hooked on the instant dictionary and the copy/paste feature for review purposes.

DeleteI am with you there, Mathew. If I could afford it I would have books in both versions, because the cut and paste is great. Maybe when I retire (in about a year) I can read more e-books because I can read them in the day and not impact my sleep.

Delete