There was a

character actor who always got bumped off in movies I watched as a

kid. Soon as I saw him on the screen, as a hotel clerk, a

barkeep--someone who stumbles into a holdup or some other criminal

activity, which was the only kind of role I remember seeing him in, I

knew instantly he was about to get bumped off, as he was never

onscreen long enough to develop any role other than victim. I don't

know his name, but I can see his dumpy little body clearly and hear

the high-pitched, nervous, raspy voice. which reminded me of the Snow

White dwarf "Doc," begging desperately not to get bumped

off. I've Googled until my fingers screamed, trying every which way

to identify this putz, to no avail. I may even have added "born

with bump

me off

tattooed on his butt" to my Googling. You'd think someone at

Google would have felt a little compassion for me, steered me in the

right direction. But...

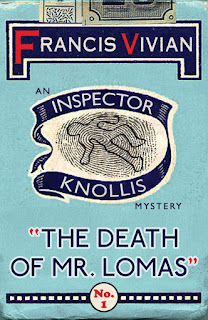

If The

Death of Mr. Lomas

had been made into a movie back in the day (the book was published in

1941) guess who would have played Mr. Lomas? I'll let author Francis

Vivian give you a clue—the first paragraph of the prologue:

He was a

little old man with shrewd grey eyes. He had a yellowish goatee

beard, a moustache with waxed points, and bushy eyebrows. His

nostrils were twitching and his lips quavering when he called on the

Chief Constable of Burnham early that fine June morning. He allowed

himself no more than the front edge of the chair with which he was

provided and each time his eyes met those of the Chief Constable they

retreated behind

their

lids like the horns of a snail.

A little

later, still in the chief constable's office, the little old man

comes to the point:

"Mr. Lomas wriggled on his inch of chair. His beard quavered

ridiculously as he tried to force words from his throat. He opened

his mouth twice, only to close it again...[and] eventually gripped

the arms of the chair and leaned forward. 'I am being poisoned, Sir

Wilfred!' he said dramatically." Sir Wilfred, of course, thinks

him a kook, and dismisses him,

But later

that day...oh yes...Mr. Lomas indeed turns up dead. His beard had

been shaved off postmortem. Tests soon establish fatal

cocaine poisoning.

It's

probably a good thing this observation by local police Inspector

Gordon Knollis didn't appear until chapter eleven or one might have

wondered by then if the honorable protagonist of Vivian's ten

Inspector Knollis cases was in fact quite so honorable, or was at

best full of baloney:

"...this is no story-book case, and there will be no surprise

ending. The most obvious person killed him, for the commonest and

most obvious reason. That person went about it in the simplest

possible way, and, paradoxically, it

is the factor of simplicity that has proved the complication in the

case.”

Well,

maybe in Knollis's mind. In my mind that statement, especially by

chapter eleven, is laughable. A veritable horde of suspects emerged

almost immediately after Mr. Lomas's OD. Among them are his dentist

son and spinster daughter, who stand to inherit a sizable cash

estate, a pharmacist "best friend" who loved Lomas's

mistreated wife (who died recently), the son's mysterious girlfriend,

and assorted other vaguely sinister characters. Complementing these

suspects

with their motives, means, and personalities was the early discovery

Lomas had been a prickly, miserly SOB more akin to the fairytale

troll under the bridge than the lovable Dwarf Doc impression I'd

somehow conjured at the start. And despite Knollis's denial of

complications, this, with its multitude of secretive, potential

poisoners,

was one of the most complicated crime novels I've ever read. It took

Knollis, with his assistants, to probe and unravel and theorize and

analyze and puzzle the pieces together to...well let's let him

explain:

"I

always wanted to be an engineer," he tells his wife, "to

take things to pieces and put them together again; I always wanted to

know how things work, and why they work.”

She smiled,

the loyal wife boosting her hubby's self-confidence. “Doesn’t

that prove that you have a flair for detection? You deal with men’s

minds, motives, and desires. You dissect their actions, theorize on

why they do this, and that, and the other; on how they could have

done this, and that, and the other. You are just as much an engineer

as if you were dealing with engines and machinery.”

She allows

a little humor into the mood by telling him, “you

look like a detective.”

This

revelation was most welcome with me, as my introduction to the

Knollis series had been book six, The

Singing Masons,

in which he's now with Scotland Yard and is assigned to aid local

constables stuck with a most unusual murder among several beekeepers

and their families. The

Death of Mr. Lomas

is the series debut, providing us an introduction to its star.

Knollis,

the author tells us, "looked more like a detective than anything

Hollywood could produce in its most enthusiastic moments. He might

have been taken from stock. He was lean, and had a long inquisitive

nose that was destined to be thrust into mysteries whether mechanical

or psychological. His eyes were of a cold grey hue, mere slits

through which he regarded the world with suspicion. They were

forbidding until the creases at the corners were noticed, but it was

seldom they came into play unless he was relaxing in his wife’s

company or playing bears with the two infant versions of himself who

were now safely tucked up in the nursery above them. Knollis’s

major trait was patience, a fact thoroughly appreciated both by his

wife and by the officers with whom he worked;

it was his patience that had enabled him to rise from a uniformed

constable on beat to the head of the Burnham Criminal Investigation

Department. He was now forty-one years of age, and eminently

satisfied with his lot."

So there. Sort of a

modernized, domesticized version of Sherlock Holmes. Basil Rathbone

would have been perfect.

There

are some disturbing, as well as eye-rolling moments in the narrative

attributable presumably

to

the WWII-era majority public sensibility.

We have curtains described as nigger-brown,

and physical features suggesting moral turpitude, such as the

description of Lomas's dentist son as “clear-eyed and

fresh-complexioned. His jaw was tight, but Knollis, from long

experience, recognized signs of moral weakness in the curve of the

chin and the sloping angle of the jaw.” Gotta wonder how many male

readers reflexively reached for their own jaws after reading that

line. Alas

I,

of impeccably

adequate

moral strength, succumbed, as

well,

dammit.

This one still holds, tho, I

submit: “I cannot understand the ramifications of the female

mind.”

Vivian

leaves us with one mystery unsolved. Perhaps more can be learned in

later episodes:

Knollis

calls his typewriter “George.”

This

just in:

My

friends at Google evidently have been reading over my shoulder, as

they just now have surprised me with a gift! The guy from whom I

learned as a young, impressionable moviegoer never to beg murderers

for mercy was Mr. Percy Helton. May he rest in peace at long, long

last.

[For

more Friday's Forgotten Books check the links on Patti

Abbott's unforgettable blog]

Mathew – You nailed it. Percy Helton matches your description. He was in a ton of movies and TV shows. Check out his IMDb page:

ReplyDeletehttps://www.imdb.com/name/nm0375887/?ref_=ttfc_fc_cl_t3

Good idea. Thanks, Elgin!

DeleteMerry X'Mas and a Happy New Year to you and your loved ones, Mathew.

ReplyDeleteMany thanks, Neeru, and may you and yours enjoy the season, as well!

Delete