I

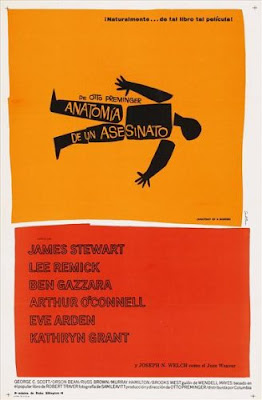

didn't learn until two days ago, six decades after watching the movie

adaptation of Anatomy

of a Murder

with

my parents, that "Robert Traver" based his novel on a real

murder case and that he had been the defense attorney in that case. I

vaguely recall comments to that effect by my lawyer father. If so

he'd have gotten it from newspaper accounts, as there's no mention of

it in the movie or in the novel. My memory on this is cautious

because I also believed my father had said the author, whose real

name was John D. Voelker, a Michigan Supreme Court Justice when he

wrote the novel, had played the judge in the movie.

'Tweren't so. The

man playing the judge was vastly more important historically than a

hundred Judge Voelkers or even a hundred Jimmy Stewarts, the actor

who brilliantly portrayed Voelker's real-life trial role in the

movie. I sit chagrined now by this flawed memory, as Dad, who spent

the years I knew him deriding "McCarthyism" whenever he saw

so much as a hair from its ugly head, would never have mistaken a

mere state supreme court justice for Joseph N. Welch, the Boston

attorney who five years earlier called the Wisconsin demagogue's

bluff in the Army-McCarthy hearings with this single line, which I do

remember hearing live on the radio at the time but without remotely

comprehending its thunderous significance:

"Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last?"

Although

I’ve thought of that movie often over the years, I never read the

book—until last week. It’s a long’n at 437 pages, yet, despite

length and wordiness, it pulled me through with a relentless force.

As is often the case for me, voice has a lot to do with how I take to

a novel. With Anatomy

of a Murder I

found myself astounded by the unmistakable, ingenuous, unashamedly

corny voice of Jimmy Stewart! Want a sample? Here’s the novel’s

narrator, Paul Biegler, lamenting the loss of his job as county

prosecutor to a young Korean War veteran (Biegler was 4F), and

wondering what he should do with the rest of his life:

“For

a spell I even dabbled with the heady notion of organizing a sort of

American legion of 4F’s. We’d have an annual convention and

boyishly tip over buses and streetcars and get ourselves a national

commander who could bray in high C and sound off on everything under

the sun; we’d even get a lobby in Washington and wave the Flag and

praise the Lord and damn the United Nations and periodically swarm

out like locusts selling crepe-paper flowers or raffle tickets or

some damned thing, just like all the other outfits.”

J-J-James

Shtowert, no? Anyway, I heard him in there, all the way. It was

Stewart I remembered most from movie, notwithstanding Lee Remick’s

skintight

slitherings

and come hitherings and enrapturing smile and eyes and...things. And

the scene I remembered most fondly, and which almost seduced me into

taking up trout fishing and smoking Italian cheroots, was the opening

scene:

Duke Ellington’s saucy jazz riffs accompanying a tiny convertible

in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula zipping along a winding road until

the car’s in front of us and we see it’s Stewart driving and it’s

early morning and he slows down through the little town and waves and

speaks to a shopkeeper and finally arrives home and stashes his

freshly caught trout in the fridge with several dozen other trout,

each wrapped in newspaper, stows his fishing gear in a sort of

hallway/closet and then…

I’ve

played that scene in my mind over and over again over the decades,

and it always faded out with me playing the Jimmy Stewart part. But I

never studied law or learned to fish with a fly. But last week, for

no particular reason save perhaps some sort of irresistible impulse,

I bought the DVD and played the movie once again. Alas, to my

heartsick disappointment the opening had shrunk over the years. The

convertible now is already entering the town instead of winding along

through the countryside—a scene I’m now thinking was in the

theatrical version I saw but was cut in later editions to pare down

the time of this still quite long—about two hours—fictional

dramatization of a real trial that successfully tested a 19th

century Michigan Supreme Court ruling that affirmed

the concept of dissociative reaction, aka “irresistible impulse,”

as a legitimate insanity defense. It established Michigan as one of

only a few states to recognize this defense as valid, legally

exonerating someone who, whether or not able to distinguish between

right and wrong at the time, simply cannot resist committing the

crime.

Both

cases—the real and the fictitious—involved a military man

shooting to death the proprietor of an inn after the proprietor raped

the soldier’s wife. Both defendants were tried by jury, and both

juries rendered the same verdict. The two main difficulties Anatomy’s

defense face are to convince the jury that the victim did in fact

rape the defendant’s wife and that her husband was in such a mental

state after seeing what had happened to her that he marched straight

from the couple’s trailer to the inn and emptied his war trophy

German Lüger

into the rapist. Complicating both requirements are the stunning

beauty of the wife and the jealous nature of her soldier husband,

both of which could be seen in the couple’s courtroom demeanor. In

the movie, the wife, played by Lee Remick, made this more difficult

for her husband by flaunting her flirtatiousness around the small

town where the trial was being held. The wife is more restrained in

the novel, but still comes across as strikingly attractive. Here’s

Biegler, her husband’s, lawyer, describing his reaction to meeting

her:

“I

caught my breath. Her eyes were large and a sort of luminous aquarium

green. Looking into them was like peering into the depths of the sea.

I had never seen anything quite like them before and I was beginning,

however dimly, to understand a little what it was that might have

driven Barney Quill off his rocker. The woman was breathtakingly

attractive, disturbingly so, in a sort of vibrant electric way. Her

femaleness was blatant to the point of flamboyance; there was

something steamily tropical about her; she was, there was no other

word for it, shockingly desirable.”

Yet,

more engrossing than the drama these primal dynamics bring to

Anatomy,

the novel takes us into a world seldom seen in such depth and

intimacy by the average citizen, that of trial by jury. Even Biegler

is amazed to realize in the heat of this courtroom battle the

contest’s ultimate vitality. “A

grim thought suddenly assailed me,” he tells us. “Though I had

never held many illusions to the contrary, I was now struck solidly

in the gut with the notion of what a snarling jungle a trial really

was; with the fact that despite all the obeisant “Your honors”

and “may it please the courts,” despite all the rules and

objections and soft illusion of decorum, a trial was after all a

savage and primitive battle for survival itself.”

Of

Biegler’s love for this high-stakes arena there is no doubt. He

compares the practice

of law with prostitution, “one of the last of the unpredictable

professions—both employ the seductive arts, both try to display

their wares to the best advantage, and both must pretend

enthusiastically to woo total strangers.”

And

of a murder trial? “A lawyer caught in the toils of a murder case

is like a man newly fallen in love:

his involvement is total. All he can think about, talk about, brood

about, dream about, is his case, his lovely lousy goddam case.

Whether fishing, shaving, even lying up with a dame, it is always

there, the pulsing eternal insistent thump thump of his case. Alas,

it is true: the lover in love and the lawyer in murder share equally

one of the most exquisite, baffling, delightful, frustrating,

exhilarating, fatiguing, intriguing experiences known to man.” A

lot like writing a novel, author Voelker might have added.

As

to the movie’s opening scene...the one I’d held in my memory

since 1959 of the aerial view of the convertible flying along the

winding road, and the saucy jazz, I began to wonder if maybe my

imagination had gotten involved a tad too much in there. If so, I’d

have to admit to being an unreliable witness, and would be wary of

inflicting my memory on anyone who might find his or her life or

freedom on trial by a jury. I figured if the scene had been cut in

the DVD version I watched two days ago maybe I’d find it in the

book. And were that so, I would be exonerated. Sadly, this was not to

be. Here’s the opening, wonderful as it is, but not what I needed

to restore my confidence. If you have a Duke Ellington CD handy, for

Pete’s sake (as Jimmy might have put it) put it on:

|

| Otto Preminger and John D. "Robert Traver" Voelker |

“The

mine whistles were tooting midnight as I drove down Main Street hill.

It was a warm moonlit Sunday night in mid-August and I was arriving

home from a long weekend of trout fishing in the Oxbow Lake district

with my old hermit friend Danny McGinnis, who lives there all year

round. I swung over on Hematite Street to look at my mother’s

house— the same gaunt white frame house on the corner where I was

born. As my car turned the corner the headlights swept the rows of

tall drooping elms planted by my father when he was a young man—

much younger than I— and gleamed bluely on the darkened windows. My

mother Belle was still away visiting my married sister and she had

enjoined me to keep an eye on the place. Well, I had looked and lo!

like the flag, the old house was still there.

“I

swung around downtown and slowed down to miss a solitary drunk

emerging blindly from the Tripoli Bar and out upon the street, in a

sort of gangling somnambulistic trot, pursued on his way by the

hollow roar of a juke box from the garishly lit and empty bar.

“Sunstroke,” I murmured absently. “Simply a crazed victim of

the midnight sun.” As I parked my mud-spattered coupe alongside the

Miners’ State Bank, across from my office over the dime store, I

reflected that there were few more forlorn and lonely sounds in the

world than the midnight wail of a juke box in a deserted small town,

those raucous proclamations of joy and fun where, instead, there

dwelt only fatigue and hangover and boredom. To me the wavering hoot

of an owl sounds utterly gay by comparison.

“I

unlocked the car trunk and took out my packsack and two

aluminum-cased fly rods and a handbag and rested them on the curb. I

shouldered the packsack and grabbed up the other stuff and started

across the echoing empty street.”

[For

more Friday's Forgotten Books check the links on Patti

Abbott's unforgettable blog]

I’ve owned a paperback of this book for years, but never read it. I’ve seen the film several times and I consider it a great movie with a great cast.

ReplyDeleteI found the book at least a third longer than it had to be, Elgin. Still well worth the time. Really gets into the nuts and bolts of a murder trial.

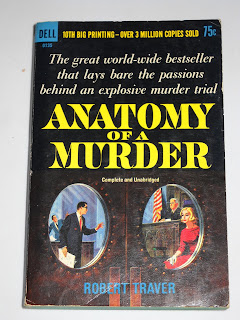

DeleteI also have had a paperback copy of this book for years and not read it yet. I am going to go see if it is the same one pictured here. But I haven't seen the movie either. Maybe the length of the book has been deterring me, but I should read it anyway.

ReplyDeleteI think this is one book/movie combo where seeing the movie first might be the best way to approach the novel, Tracy. It was for me. The movie takes enough liberties with the book's plot that there will be surprises there, as well.

Delete