I doubt I'd

have been able to discuss The

Echo Maker

if I hadn't found something I thought was wrong with it. It's almost

too daunting. "You stagger out of Powers’s novel happy to find

yourself, like Scrooge the morning after, grasping your own bedpost,

saying 'There’s no place like home,'" says Margaret

Atwood in The New York Review of Books,

"and

hoping you still have a chance to set things right."

And Patrick

Ness in The Guardian:

"His books seem wrought rather than written, and try as he

might, he can't help but make you feel just that little bit stupid."

I feel a

little bit like Homer Simpson would trying to write about Finnegan's

Wake,

but I’m too stubborn to shirk making an effort, if only just to

stitch together some of the erudite observations by vastly more

sophisticated readers who dared to step forward and put them on the

record. The

Echo Maker,

after all, is a must read for anyone busy being born, not

busy dying (to steal shamelessly from a Nobel laureate).

And

for those readers perched on the edge of their seats eagerly seeking

an opening to accuse me of oversimplification with my

observations, I hereby address their indubitably accurate assessment

right here and now:

The core notion in both Richard Powers novels I've read—The

Echo Maker

and The

Overstory—condemns

the human species as having evolved too far for its own good. We've

come to know too much about too little, and too little about too

much. In even simpler terms, because our lizard brains continue to

call the shots despite what our higher intellect knows to be true, we

are doomed. Powers brings the humility to us more delicately with

this quote from Loren Eiseley's The

Immense Journey:

As for men, those myriad

little detached ponds with their own swarming corpuscular life, what

were they but a way that water has of going about beyond the reach of

rivers?

Be assured,

Powers is a preacher. A preacher in the mold of those 18th

century Boston Unitarian pulpiteers whose eloquent oratory nudged

statesmen, merchants, and the general citizenry to set their sights a

tad higher than base appetite and self-servitude. Morality for the

sake of a civil society was the impetus then. It was good for

everyone for each to be good. Not enough anymore, Powers contends. In

fact it's likely way too late for good by anyone to do most anyone

any good beyond the short-term illusion. As someone in the Bible must

have said or at least pondered, we've pretty much sealed our fate.

[MOMENTARY

INTERMISSION FOR WEEPING, EXCHANGING HUGS, BLOWING NOSES, AND

RETURNING TO SEATS TO LEARN WHAT RICHARD POWERS DID WRONG IN THE

ECHO MAKER]

Yes, I am

most grateful to have found something to carp about in this

incredibly, brilliantly overwhelming novel. It has to do with neither

plot, science, philosophy, conjecture, or fluidity of thought, all of

which contribute to the overall disquieting effect of The

Echo Maker.

My quibble is with the humble element of the writer's craft, about which I

will have more to say after a brief synopsis/discussion of the

astonishing features alluded to in the previous sentence. I probably

shouldn't have said "brief," as I doubt I can be as concise

as I, and you, most certainly would prefer. But please bear with me.

I shall try, we shall see.

Powers

brings his scenario of doom to us in the guise of several seemingly

disparate narrative rivulets, each engaging us in its own way as it

meanders through crises of purpose and identity edging incrementally

closer to the others with a momentum toward confluence

in a larger, more portentous story. A key to Powers's power is a

storytelling gift that enables him to deliver conclusions from his

boundless intellect in a palatable embrace accessible to curious

muddlers like me. And Powers understands the importance of story,

most likely more keenly than I, who without question would stumble

pitiably off the foot bridge to understanding his wizardry without

the rope of story to hold onto to steady my nerves. One of the

principal characters in The

Echo Maker,

a cognitive neurologist, emphasizes its fundamental importance:

Consciousness works by telling

a story, one that is whole, continuous, and stable. When that story

breaks, consciousness rewrites it. Each revised draft claims to be

the original. And so, when disease or accident interrupts us, we’re

often the last to know.

The novel’s

plot unfolds in the minds of three individuals besides the cognitive

neurologist:

a young man with brain damage who believes his sister is an imposter;

the sister, who tries mightily to convince him she’s real, and

Powers, constantly looking over everyone’s shoulder explaining what

they see and are thinking, And there’s the irritation for me:

too much ‘splaining and not enough showing. His kibitzing intrudes

needlessly, tediously, and, as one professional reviewer put it, the

prose lacks levity. Powers’s voice here brings to mind the

brightest kid in class forever displaying his superior knowledge. The

kind eager to explain in minute detail, without himself laughing, why

a joke is funny. Possibly the only aspect of human cognizance Powers

either doesn’t get or is blind to for its narrative value is

subtlety.

Yet these shortcomings are

mere nit specks in the extraordinary tapestry he has woven for us

to make his point that we just might yet have a miniscule chance of

getting our shit together in time to avoid flushing ourselves down

the toilet of extinction.

He uses as

an analogy the marvelously mysterious sandhill crane, known by the

very earliest Americans as “echo makers” for their unearthly

cries. “All the humans revered Crane, the great orator,” Powers

explains. “Where cranes gathered, their speech carried miles. The

Aztecs called themselves the Crane People. One of the Anishinaabe

clans was named the Cranes—Ajijak or Businassee—the

Echo Makers.

The Cranes were leaders, voices that called all people together. Crow

and Cheyenne carved cranes’ leg bones into hollow flutes, echoing

the echo maker.

“Tecumseh

tried to unite the scattered nations under the banner of Crane

Power,’ Powers tells us, “but the Hopi mark for the crane’s

foot became the world’s peace symbol. The crane’s foot—pie

de grue—became

that genealogist’s mark of branching descent, pedigree.”

These long-legged, graceful

dancing birds land by the hundreds of thousands every year in a

Nebraska marsh on their seasonal migrations. Two former lovers of the

brain-damaged man’s sister are adversaries over disposition of the

wetlands that host these legendary birds. One is a preservationist,

the other a developer scheming to build a tourist facility to

celebrate the birds in an ironic twist destroying their habitat.

“One

million species heading toward extinction,” says Daniel, one of the

sister’s lovers. “We can’t be too choosy about our private

paths.”

The

sister muses, “Something in Daniel mourned more than the cranes. He

needed humans to rise to their station:

conscious and godlike, nature’s one shot at knowing and preserving

itself. Instead, the one aware animal in creation had torched the

place.”

One might

think these details thicken the plot enough already. One would be

wrong. It gets plenty thicker. Much of The

Echo Maker

has to do with the brain, of humans and others. My Homer Simpson

wisdom ventures a guess that what Powers is doing with his dazzling

exposition of cutting-edge neurological science is to show us how

fractured we are, how amorphous and shifting is our sense of who we

are and what we are, and how terribly wee we are in the cosmic scheme

of it all.

Powers gives us science so

mind-blitzing we can’t help but wonder at its veracity, yet we know

from others who’ve done their Googling that it’s real. Anecdotes

of people whose lives have been horribly deranged by injury or

changes in their brain chemistry are enough to make me consider

wearing a football helmet

everywhere, even to bed.

Alright now

here’s something that if it isn’t true Powers ought to be tarred

and covered with crane feathers and made to get a better haircut. The

following whacked me especially hard upside the head because I had

exactly the described experience back in the day, although it wasn’t

induced in the same way. No stream of electrodes was employed;

mine came with the so-called illegal smile. Here’s the one with the

juice (big words be damned):

Consider

autoscopy and out-of-body experience. Neuroscientists in Geneva

concluded that the events resulted from paroxysmal cerebral

dysfunctions of the temporoparietal junction. A little electrical

current to the proper spot in the right parietal cortex, and anyone

could be made to float up to the ceiling and gaze back down on their

abandoned body.

Wondering

now if maybe that smile of mine (or its motivator) didn’t generate

a certain mellow sort of buzz in my right parietal

cortex. As it happened, I’d been watching Sam Ervin on TV gently

interrogating White House Special Counsel John Dean.

In

addition to the exhausting mystery of our brain, a more mundane

question hovers over one of the narrative threads in The

Echo Maker.

Mark, the brain-damaged man, doesn’t remember how he came to flip

his truck on a straightaway (albeit while driving some 80 m.p.h. at

night) leaving him trapped under the three tons of steel in a marsh

during the migrating sandhill crane layover. Author Powers gradually

feeds us random clues, which, as all good mystery yarns should,

merely awaken new questions and speculations as momentum builds to

the solution, which, I daresay, is a lollapalooza.

Did I say

there was no humor in The

Echo Maker?

I trust I didn’t put it quite like that. Something did give me a

pretty good laugh, before a sudden lump in my throat made the verbal

mirth sound a tad hollow. Here’s what caused the confusion:

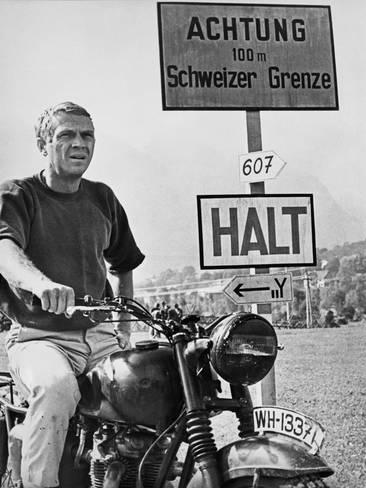

“This

is it. Carhenge,” says the brain scientist to his female companion.

(They’re on a Nebraska road trip.) The huge gray stones turn into

automobiles. Three dozen spray-painted junkers stood on end or draped

as lintels across one another. A perfect replica. They are out of the

car, walking around the standing circle. He manages a pained

imitation of mirth. Here it is:

the ideal memorial for the blinding skyrocket of humans, natural

selection’s brief experiment with awareness. And everywhere,

thousands of sparrows nest in the rusted axles.

|

| Carhenge |

[For

more Friday's Forgotten Books check the links on Patti

Abbott's unforgettable blog]