Puzzled to find Willie Black

still employed at the same dying Richmond, Va., daily newspaper after

seven Pulitzer-worthy investigative reports. With such success one

would think he'd be starring at one of the larger metropolitan

mainstream papers. I suppose it might have something to do with his

heavy drinking and lack of reverence for his bosses. At the same

time, he clearly draws his success as a reporter from the tough

Oregon Hill neighborhood where he grew up and remains.

I met him

first last week reading Oregon

Hill,

the debut of his eight first-person accounts solving murders in the

Richmond area. Oregon

Hill

so impressed me with its authenticity--the narrator's voice and the

feel of both the inside of a newsroom and the city it covers, the

bone-depth depictions of its gritty characters and their true

dialogue, the compelling story, and...have I forgotten anything? Oh,

of course...the simply fine, smooth, engaging craftsmanship! So is

Evergreen

the second in the Willie Black series? No indeed!

It’s

become a habit—and I’m not really sure why—that when I’ve

read the first of a series that’s new to me, and I like it, I jump

ahead and next read the most recent. Partly, I suppose, it’s to see

if the latest adventure lives up to the promise of the first. I’ve

found that some writers seem to fall into a rut, maybe grow tired of

their characters and sort of go on auto-pilot eventually. Happy to

report this is not the case with Evergreen,

book eight (and I hope still counting). Altho I have yet to read the

six books in between, now that I’ve bracketed them with the first

and the last, I’m confident I will read them all—as long as

Willie’s around to live them and tell us what happens.

|

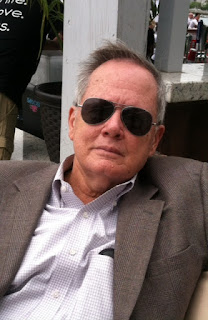

| Howard Owen |

As to

Evergreen,

a vivid clue to its story can be found in its rather grim cover,

depicting the kind of spooky old abandoned cemetery one might expect

to find illustrating something by Edgar Allen Poe, some Gothic tale

with gloom and ghosts, and doom in the mix. Clearing up that mystery

right now, I assure you there’s nothing spectral infringing upon

the sensibilities of the living characters in Evergreen.

This is not a ripoff of Kolchak

the Night Stalker.

Here the dead remain dead from beginning to end—except, if you

will, in the minds of the living. In particular the mind of Willie

Black, whose long-dead father is brought to mind on New Year’s Day

by the woman who’s been tending his grave ever since he died

mysteriously when Willie was an infant. The woman, Philomena

Slade, is on her deathbed. Her son, Richard, informs Willie,

awakening him from an unusually hellacious hangover.

Without knowing why, Willie goes to see her at the hospital. He tells

us why he dragged himself from bed, where his fourth wife lay asleep

wearing a pair of men’s underpants around her neck:

“Richard

Slade once did nearly half a lifetime for a rape he didn’t commit,

and he almost spent the other half in prison for a murder that also

was done by someone else. In my never-ending quest for truth,

justice, and cheap-ass Virginia Press Association awards, I helped

keep that from happening, so we do have some history. And, oh yeah,

he’s my cousin, somewhat removed.”

Neither

Willie nor his mother had ever been to his grave in the long

abandoned Evergreen

Cemetery. “Somewhere on the eastern edge of the city, out in that

no-man’s land between the projects and the country.” Willie’s

mother, had never wanted to talk with Willie about his

African-American father. who’d lived with a succession of men since

the death of Artie Lee, the light-skinned jazz saxophonist she’d

fallen in love with as a teenager.

“He

died before I was talking. I have almost no memory of him,” Willie

tells us. “He and Peggy never got married, mostly because I was

born seven years before the Supreme Court forced the Commonwealth of

Virginia to let African Americans and white folks marry each other.”

He doesn’t relish taking up the gravekeeping task from Philomena,

but she’s persistent. She’d been a friend of Willie’s mother

since before he was born. Probably more persuasive, Philomena is

“a tough old broad who will haunt me from the grave if I don’t

follow through.”

So

he does, and his first visit to the grave sparks a curiosity about

the man who’d sired him. He begins digging into records and old

local denizens who know Artie Lee. It soon becomes clear that no one

wishes to dig up the past regarding Lee’s single-vehicle fatal

accident Willie learns had been “witnessed” by at least three

unnamed people. He persuades his bosses he’s working on a story

about his father to run as a feature on Father’s Day, but he

immerses himself into this sleuthing through prior years as if

looking for the corpse of Jimmy Hoffa. He

learns a

little bit here and there

from a couple of Artie’s surviving bandmates, who inch toward what

they seem to know happened but stop dead before the reveal, and from

Willie’s old adversary, the Richmond police chief, who reluctantly

feeds him a couple of clues on strict, not-for-attribution-to-anyone

background. But his first big break in solving the riddle comes while

pouring through old newspapers published around the time of his

father’s death. He stumbles onto this small headline:

Negro

man killed/ in Charles City crash.

“The story was eight paragraphs long. My father was the lone

occupant of the car, the story said. The wreck happened about nine

p.m. The car hit a tree, and that was it for Artie Lee, who, our rag

reported, died at the scene. The last paragraph:

A

witness who was walking along Route 5 claimed he saw two other men

standing alongside Lee’s car, stopped on the highway, but he

couldn’t identify them. Police are investigating.

With more interviews leading

to more filament leads, it’s another news clip that flips the light

on in Willie’s head. Story about a Klan rally in which a cop and

his girlfriend were killed when a bomb exploded under the police car

they were “huddling” in. Willie learns the identities of the two

cops who investigated this killing. One of them was still alive,

barely, but when Willie confronts him he essentially admits to what

he knows happened. There are other revelations that tell us, and

Willie, why no one wanted to open the can of worms involving Artie

Lee’s suspicious death.

As

the Bard titled one of “his” plays, All’s Well That Ends Well.

Not sure the ending of Evergreen is as well as some of us might like,

but it does end. Definitively.

“When

Faulkner said the past isn’t even past,” Willie muses, “he must

have been thinking about Richmond in general and my own tangled life

in particular. Everywhere I go, history jumps out of the bushes and

nips at my heels.”

|

| Klan march several blocks from Virginia State Capitol, circa 1925 |

Have I said I’ll probly read

the other six Willie Black tales? Either way, I’m removing the

“probly,” and letting the rest stand.

I will definitely look for books by Howard Owen, Mathew. First I will try the annual book sale, which is coming up soon, then look online. Thanks for another interesting review.

ReplyDeleteI think his style is right up your alley, Tracy.

Delete