It’s

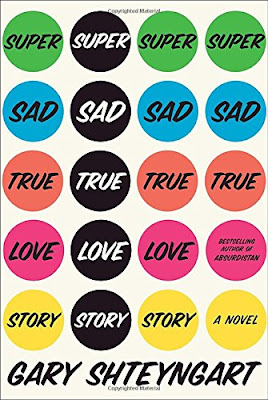

taken me three readings of Gary Shteyngart’s Super

Sad True Love Story

to recognize finally my vague discomfort accepting the presumption

of sadness at this exceptional novel’s ironic ending. That’s one

reading every three years starting with 2013, three years after its

publication. The trienniality is coincidental—unless, as suggested

by Shteyngart’s Tweeted tribute quote on the death last week of his

beloved Random House editor Susan Kamil,

"He did believe, dimly, in a democracy of ghosts. The souls of

the dead, perhaps formed committees, and these, in continuous

session, attended to the destinies of the quick."

It’s

from Nabokov’s

novel Pnin.

Shteyngart added, “I would like to believe this is true. Farewell

Susan.”

Accepting

it as true, why not take it a step further and believe one of these

dead souls’ “committees” has been goading me to fathom the

elusive mix of emotions I experience at Super

Sad’s

ending? Not that it would matter particularly to anyone else. And

yet, there is a confluence of sorts that might well be calling to

certain of the

quick

to, in a social media vernacular, “Get off your asses, and be quick

about it!”

I

feel this urgency. It’s the reason I’ve started reading William

Vollmann’s massive two-volume report on the virtual demise of our

species. In the first third of Carbon

Ideologies,

which is as far as I’ve gotten, Vollmann’s focus is on the

nuclear generating disaster at Fukushima,

Japan in 2011 (a year after Super

Sad

was published). He’s written it as an explanation to possible

survivors of what he sees as inevitable climate catastrophe. His

writing is framed as an apology to future inhabitants of Earth, and,

less directly by presuming its inescapability, scaring the living

crap out of those of us who still entertain an implausible hope of

somehow averting the disaster. “I knew I’d find no adequate

personal answer to the question ‘What should we do?’” he tells

these theoretical survivors, “But

I felt ashamed of doing nothing.

Well, in the end I did nothing just the same, and the same went for

most everyone I knew. This book may help you in the hot dark future

to understand why.”

|

| Gary Shteyngart |

I feel the urgency also

because of the political imbroglio we’ve permitted that exacerbates

the disparities in our society, and because of the growing passivity

of a culture easily distracted and manipulated by cheap

entertainment, with its expectations of titillation, comfort, and the

illusion of freedom.

This

awareness was less defined when I first read Super

Sad True Love Story,

which I was enticed to read by a review Maureen Corrigan broadcast on

NPR. What got my attention, perked my interest, induced me to buy the

book was Corrigan’s description of a fictional near future that

struck me as already incipient in its drift toward a junction of

chaos and control. It rang of Orwell and Huxley, 1984

and Brave

New World,

but with comic twists and an endearing familiarity. As then New York

Times critic Michiko Kakutani put it, “Mr. Shteyngart has

extrapolated every toxic development already at large in America to

farcical extremes.”

Reading

it the first time I focused on the distance between then and

Shteyngart’s fictional future. And, of course, there was no

avoiding the love

story between 39-year-old second-generation Russian Jewish immigrant

Lenny Abramov and 24-year-old second-generation Korean immigrant

Eunice Parks. This story, told by way of diary entries and social

media conversations, provides the narrative train through Super

Sad’s

dystopian landscape, yet I found my interest veering more toward a

skeptical voyeurism than empathizing with the obviously mismatched

couple. Whether the concept of true love is realized between Lenny

and Eunice, who could say with any certainty? Kakutani clearly

thought so, as did several other reviewers who discussed the book at

the time. I see the two as using one another, each for different

reasons. But maybe that

is love.

Maybe it’s only love’s illusions I recall

(thanks, Joni). I waxed enthusiastic with the brief piece I posted

here in 2013 after the first read, but not about the romance.

“At

least one of Super

Sad's

predictions, that books will become dangerously unfashionable, has

already almost come to pass,” I wrote then, adding, “It's one of

the funniest, gloomiest social satires I have encountered.”

Three

years later, after my second read, I still didn’t try to review the

book,

intimidated probably by the enthusiastic gushings of Kakutani,

Corrigan and others, including Terrence Rafferty in Slate.

Looking back, I find I like Rafferty’s best of the three reviews.

He gives more plot and details. I should condense plot and details

down for you myself but after reading the professionals

I’m stymied, as if doing so would be akin to fashioning a Fabergé

egg out of paper-mâché.

Instead I’ll give you a link to Rafferty’s review:

here.

So,

there you have it, something you can hold against me forever,

depending on how much “forever” we have left to live. A book I’ve

read three times over the past six years, and still

haven’t gotten up the gumption to do it justice. And yet, still, on

the verge of hysteria, I implore you to read the damned book BEFORE

IT’S TOO LATE!!

Back now to William Vollmann’s

horrifying apology to whomever might still be alive after the planet

that’s hosted us all these eons finally turns out the lights…

Wait! I just went back and re-read

the ending, the last chapter, one more time. I see now the cause of

some of the ambivalence I’ve been feeling about it: I wasn’t

ready for so abrupt a change in tempo. The main narrative had me

rushing, frantically, to the apocalyptic edge, the unendurable

sensation of imminent void. The last chapter, "27 – Welcome Back,

Pa’dner,” begins with a sense of free-fall, a little relevant

backstory, just enuf to offer the racing mind a more contemplative

speed. It works, I suspect, for most readers. Not for me. My

cognition is sluggish, slower to shift. My inner brakes were

screaming as I tried to decipher how the words I was reading fit with my despairing terror of the calamitous denouement I'd been approaching. Then the

cinematic break taking me from Kansas sepia to the Technicolor of

Oz. Stumbling with contradictions, my ambivalent feet carried me to a

place where at last I could sit and sort things out. And where I

could appreciate the language, the secret humor, the tranquility and

the beauty of simply being alive, no matter what future lay beyond

the next heartbeat. Reading this chapter a fourth time, without the

preceding headlong dash, I finally appreciated what Shteyngart had

done. And despite the title and the scrambled emotions throughout, I

believe he and I, on this point, are of one mind.

If so, this might help explain

my inability to fully embrace the sadness others have found in Super

Sad True Love Story. I see it as a sadness compromised

by foolish expectations. A vanity. A sadness we deserve.

My advice: Find out for

yourself.

[Find

more Friday's Forgotten Books links at Todd

Mason's amazingly eclectic blog]

I think you have convinced me I have to read this book, Mathew, or at least one of the fiction books by this author.

ReplyDeleteIt's the only one I've read by him, Tracy. But it really grabbed hold of me.

Delete