By

the way, The

Blessing Way

is

really The

Enemy Way, as

Tony Hillerman reveals in his memoir, Seldom

Disappointed:

“I named it The

Enemy Way

but my editor for reasons beyond my ken changed that to The

Blessing Way.”

Frankly,

my dear, I don’t give a big cahoot which Way is the

Way.

Each is way too complicated for your everyday Belacani,

yet, perhaps because of this,

all

the more

fascinating. Belacani?

That would be Navajo for “white man.” If nothing else,

Hillerman’s 18-book Navajo Tribal Police mystery series is a good

way to learn a few Navajo words along with a great deal about the

culture and religion—known collectively as “The Navajo Way”--of

these early Americans. So accurate are the Navajo depictions in these

novels they were used in Navajo schools, and earned for Hillerman the

tribe’s Special Friends of the Dineh Award.

This

is my second go at the Tony Hillerman canon. I read them all in the

‘80s after a friend recommended them. I suppose instead of

re-reading these I should leap ahead and read at least one of

the five Leaphorn/Chee mysteries

by

his daughter Anne Hillerman, written

since

Tony’s death in 2008 at age 83. Not sure why I haven’t read any

of Anne’s yet. Some sort of superstition, maybe? A witching thing?

I

can’t rule that out, but for the sake of Belacani probity I hereby

promise:

after reading People

of Darkness,

which I’ve already downloaded because altho it’s the fourth in

Tony’s series it’s the one that introduces Jim Chee, I will read

Spider

Woman’s Daughter,

the first by Anne carrying the baton from her dad.

Chee

starts in the fourth, you say? You mean...yup, Lt. Joe Leaphorn

soloed in the first three. Patterned after Tony’s friend, who was

sheriff of Hutchinson County, New Mexico, Leaphorn was to carry the

load alone forever and a day, until his agent and publisher persuaded

him to swing for the bleachers, write a “break-out” book, with

elements reaching a wider readership...

I

had started this book with Leaphorn as the central character, but by

now my vision of him was firm and fixed. Leaphorn, with his master’s

degree in anthropology, was much too sophisticated to show the

interest I wanted him to show in all this. The idea wasn’t working.

This is the artistic motive. Behind that was disgruntlement. If any

of my books ever did make it into the movies, why share the loot

needlessly? Add greed to art and the motivation is complete. Thus I

produce Jim Chee, younger, much less assimilated, more traditional,

just the man I needed.

Not

sure which I read first as my introduction to the series, but I’m

pretty sure Chee was in it, because in my recollection when Leaphorn

eventually appeared I thought he

was the new character. Evidently someone involved with Harper &

Row’s ebook reissue chose convenience

or marketing

reach over accuracy, as the The

Blessing Way,

Tony’s first novel, is listed on Amazon.com as “A

Leaphorn

and Chee Novel Book 1.” The listing fooled even me, the Hillerman

veteran, wondering when Jim Chee would enter the picture until I

clicked over to Seldom

Disappointed

and found out what in hell was wrong.

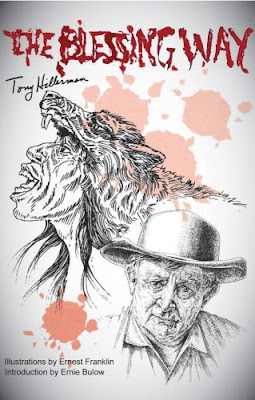

Not

that there is anything wrong with The

Blessing Way—other

than its title--which features

an

Enemy Way, a

much longer and more complex ceremony held over a three-day period to

counter the magic of a witch that’s infected an individual or

family.

A

Blessing Way involves much simpler rituals, including a sweat bath

and a medicine man’s “sing.” I’ll admit to getting thoroughly

confused reading Hillerman’s intricately detailed account of the

Enemy Way in The

Blessing Way,

where the focus is on a contagious fear among reservation families

that a witch, taking the form of a Wolf, is running amok, killing and

mutilating animals, and suspected of killing a young fugitive hiding

from police in the reservation’s cliffs and canyons.

But

I wasn’t alone. Leaphorn admits to himself to being almost

hopelessly confused as to the who and what behind the witch scare,

and why and how Luis Horseman was killed and dumped beside a public

road to be easily found by anyone happening along. Tossed into this

mix are a couple of professors doing research on the reservation, one

of them coincidentally studying the Navajo witch tradition. Hillerman

manages his complicated unusual plot with surprising skill for a

first novel. I believe a key to my quickly trusting Hillerman’s

command of the story was his having the

strong, intelligent character of Leaphorn

struggling to comprehend what was going on as well. And

I should add that far from being a police procedural, Leaphorn’s

physical presence is largely incidental to the main narrative. It’s

his mystery to solve, but other, supporting characters are drawn so

keenly and fully in their involvement, their peril, and their inner

conflicts that I found myself engaging sympathetically with them more

than with the cop. Yet, his role is so vital and indelible, and his

persistence so reliable I had no doubt ultimately he would prevail.

|

| Hillerman, UPI reporter |

Earlier

I mentioned Hillerman’s skill as a writer. As a wordsmith, a

painter of detail and panorama, sound and smell and interior

landscape, he has given us a debut novel that steals the breath away.

Here’s a scene through the eyes and senses of Dr. Bergen McKee, the

anthropologist who’s studying the Navajo witch phenomenon:

“McKee had been startled by

the sudden brighter-than-day flash of the lightning bolt. The

explosion of thunder had followed it almost instantly, setting off a

racketing barrage of echoes cannonading from the canyon cliffs. The

light breeze, shifting suddenly down canyon, carried the faintly

acrid smell of ozone released by the electrical charge and the

perfume of dampened dust and rain-struck grass. It filled McKee’s

nostrils with nostalgia.

“There was none of the odor

of steaming asphalt, dissolving dirt, and exhaust fumes trapped in

humidity which marked an urban rain. It was the smell of a country

childhood, all the more evocative because it had been forgotten. And

for the moment McKee...reveled mentally in happy recollections of

Nebraska, of cornfields, and of days when dreams still seemed real

and plausible.

“The

light of the climbing moon had moved halfway across the canyon floor.

Nothing stirred. The canyon was a crevice of immense, motionless,

brooding quiet. McKee studied the outcropping carefully, shifted his

eyes slowly down canyon, examining every shape under the flat, yellow

light, and then examining every shadow. He felt the rough surface of

the rock cutting into his knees and started to shift his weight, but

again there was the primal urging to caution.

“It

was then he caught the motion.”

For

an ex-newspaperman’s first major leap into fiction, this simply

should not have been ignored by any publisher, major or minor. That

it was, initially, because “No one will read about Indians,” says

more about the publishing biz than tales from the Rez.

I am sure I have already confessed that I have not read anything by Hillerman, but I know I should. I have this book and Dance Hall of the Dead and People of Darkness, so I have no excuse.

ReplyDeleteYou may be afraid of addiction, Tracy, which is what happened to me. I read People of Darkness over the weekend for next Friday, but I shall try to take a break from Hillerman before I'm hooked all over again. He's a masterful storyteller.

Delete