At long

last it can be alleged:

Perry Mason and his associates were in fact a highly classified cell

of fantastics working undercover for nearly forty years combating

heinous crime and prosecutorial incompetence in Southern California’s

judiciary. Their morally dicey mission:

to

save well-financed damsels in dire distress against unimaginably

implausible odds.

Mason, the

cell’s lead operative posing as a dauntless criminal defense

attorney, sheds light on the mission’s moral dilemma in this brief

exchange with his purported secretary, Della Street, while

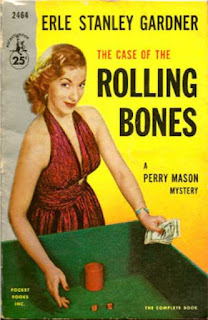

considering a potential client’s tale of woe in The

Case of the Rolling Bones:

“‘I

don’t like rich people,’ Mason said, pushing his hands down in

his pockets. ‘I like poor people.’”

“’Why?’

she asked, her voice showing her interest.”

“‘Darned

if I know,’ Mason said. ‘Rich people worry too much, and their

problems are too damn petty. They stew up a high blood pressure over

a one-point drop in the interest rate. Poor people get right down to

brass tacks: love, hunger, murder, forgery, embezzlement— things a

man can sink his teeth into, things he can sympathize with.’”

Moments

later Mason tells the distressed damsel, “If I take this case, I’ll

need money—money for my services, money for investigation. I’ll

hire a detective agency and put men to work. It’ll

be expensive.”

One might

get the notion from these two sentiments Mason didn’t like his

clients, and maybe he ddidn’t. If not, it’s the more to his

credit, as he tells the team’s uncannily effective chief

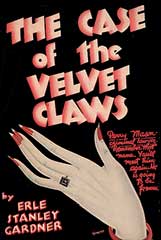

investigator Paul Drake in their debut published case, that of the

Velvet

Claws,

“It’s

sort of an obsession with me to do the best I can for a client.”

Erle

Stanley Gardner, who controlled and chronicled the activities of what

we shall call the Marvelous Mason Machine (MMM for short), gives us

vivid descriptions of these superheros introducing

them in this first of some 80 published cases. Mason, Gardner

confides, “has about

him the attitude of one who is waiting. His face in repose was like

the face of a chess player who is studying the board. That face

seldom changed expression. Only the eyes changed expression. He gave

the impression of being a thinker and a fighter, a man who could work

with infinite patience to jockey an adversary into just the right

position, and then finish him with one terrific punch.”

And later,

“His hand was well formed, long and tapering, yet the fingers

seemed filled with competent strength. It seemed the hand could have

a grip of crushing force

should

the occasion require.”

The lawyer’s “broad

shoulders” are mentioned frequently, as are references to his

athleticism and pugilistic nature. Sort of startling to encounter

this Perry Mason after years of watching stout, sedentary windbag

Raymond Burr in the TV role inspired by Mr. Gardner’s descriptions.

Similar

startling contrasts are evident with Della Street and Paul Drake. In

the original case files the two are a far cry from their bland

portrayals

on TV

by

Barbara Hale and William Hopper:

Della Street has a slim figure and steady eyes. She’s about

twenty-seven, and appears to be watching life keenly and

appreciatively, seeing “far below the surface.” Her cover story?

She came to work for MMM after her wealthy family “lost all their

money.”

And Drake, who heads the

gargantuan P.I. agency unobtrusively headquartered across the hall

from Mason’s office is tall, with “protruding glassy eyes” that

hold “a perpetual expression of droll humor,” whose shoulders

droop and head thrusts forward on a long neck.

It’s

just now occurred to me that maybe Mr. Gardner was deliberately

misleading us with his team’s physical identities. It’s entirely

reasonable he would wish to protect them in the event of reassignment

to other, perhaps even hairier undertakings

in the eternal struggle for truth, justice, and...so forth. At the

moment, however, MMM’s superpowers are

of greater interest than

their

appearances.

Granted,

on the surface Mason and his crew display attributes one might expect

in top-tier professionals of their kind--or at least which

could

be contained within mortal bounds. Mason’s NFL-linebacker’s

physique, for example, the crushing grip, the pugnacious spirit,

zen-like mental control, and I’m guessing he can make a fairly

decent omelet or poached egg in a pinch. His legal knowledge may seem

superhuman to some, but I would argue this appears so by comparison

with the theatrically dim performances of prosecutors he routinely

opposes. Fortunately Mason’s lawyerly skills are on par with those

of the judges who try his cases—men, of course, as this was a time

when even the formidable Della Street was regarded as “the girl”

by none other than Gardner himself—who always ultimately agree with

Mason despite his penchant for highly irregular courtroom practices.

One might speculate as to whether Mason’s skills extended to some

form of subtle hypnotic spellbinding of these strangely sympatico men

of the bench.

We’re

homing in here on just what it could have been beyond Mason’s

competence, both physical and jurisprudential, that elevated him to

the realm of superherodom. I postulate it was a cerebral brilliance

that impinged upon the outer limits of some mechanical contraption on

the order of, say, the Cray Supercomputer. Could it be that Perry

Mason’s brain was either somehow melded with such a device or else

had been implanted with a microchip that corresponded directly and

instantaneously with some such? Else how could he reach beyond

intuition, invariably with indomitable confidence, to know, for

example, which of the four identities assumed by a suspect in various

contexts was in fact the actual one, as he did in Rolling

Bones?

I mean Mason was supposed to be a lawyer, no? Not Carnac the

Magnificent or Sherlock Holmes, for Pete’s sake!

Which

brings us to Paul Drake, MMM’s detective but most certainly no

Sherlock Holmes, either. Yet Drake NEVER FAILED! Whenever Mason

needed someone shadowed, someone who might at that moment be sitting

across from him in the office, he’d slip a note to Della Street,

who’d slip across the hall to Drake, who’d immediately place an

operative—sometimes waiting right in the building’s elevator--to

tail the person to wherever he or she would

go.

Drake was always in his office when needed for this, and always had

plenty of operatives available at a moment’s notice. And he had

“correspondents” wherever in the world he needed them to pick up

the trail of someone or obtain information the instant Drake

contacted them.

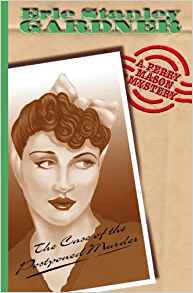

In

The

Case of the Postponed Murder,

Gardner’s last report (published three years after his death in

1970), Drake literally overnight digs up evidence of a check forgery

ostensibly committed by a missing woman Mason’s been hired to find

and help.

Mason

tells his client, claiming to be the woman’s sister, “Go see Paul

Drake. In all probability, one of his operatives can locate your

sister within twenty-four hours. If it turns out your sister is in

any difficulty and she needs legal help, I’ll still be available.”

Della Street said, “This

way, Miss Farr. I’ll take you to Mr Drake’s office.”

Next morning Drake tells Mason

what he’d learned about the forgery, and predicts he’ll locate

the woman in two or three hours.

And

we dare

not

overlook Della Street, who played a lower-keyed but equally

effective role for the team. She could whip out a steno pad and take

impeccable notes on what was being said anytime, anywhere. She also

found things the men missed, and sometimes had help from cosmic

convergence. In Rolling

Bones

she and Mason and Drake are musing over a woman Drake’s operatives

have located. They’re not sure but whether the woman’s using a

fake name. While they’re talking, Della Street is perusing the

day’s newspapers’ classifieds. Within minutes, SHAZAM!!, she hits

paydirt. “This what you want? ‘L. C. Conway, 57, to Marcia

Whittaker, 23.’ Notice of intention to wed.”

My word!

I

suppose my admiration for Mr. Gardner’s superheros

would be all the greater had they applied their powers helping the

“poor” people Mason said he preferred to the rich. But that would

be unbelievable. After all how could impecunious clients support the

most effective criminal defense law firm in Southern California and

the largest, quickest, most honest, most successful detective agency

ever known?

Could

this very, very minor oddity have

some bearing on

why Albert Einstein hid his Perry Mason paperbacks behind the heavy

physics tomes in his office at Princeton University? Relatively

speaking, of course? Because that’s where William Tangney,

Princetonian reporter later to become founding editor of Virginia’s

York Town Crier, discovered

them minutes after news of Einstein’s death reached the campus.

Had the great man been honoring MMM’s elitist reputation by keeping

its chronicles’ egalitarian publications discreetly concealed?

The prosecution rests,

uneasily.

[For

more Friday's Forgotten Books check the links on Patti

Abbott's unforgettable blog]

I have only read two of the Perry Mason series since I started blogging. One of those was TCOT Rolling Bones, and I found it so complex that I never knew who was who and what was going on. But I always enjoy the main characters... Perry, Della, and Paul. We are watching episodes of the TV series now, just finished the third season, and enjoying those also. I like all three characters in the TV series too, plus Lieutenant Tragg and DA Hamilton Burger.

ReplyDeleteMy lawyer dad made sure we watched every episode back in the day, Tracy. They were great fun. He had a bunch of the original paperbacks, too. Wish I had them now. The only one I can remember by title is TCOT Lucky Legs. Pretty sure I read it as a pre-teen, but I have no recollection of what it was about.

ReplyDeleteThe first one I read, at the age of 12, was TCOT VAGABOND VIRGIN. I was so hooked I read another dozen one after the other. By then I was so oversaturated, it was quite a few years before I read another. But over the decades I've read about 30 of them, most recently in January of this year: TCOT SLEEPWALKER'S NIECE (https://kevintipplescorner.blogspot.com/2018/01/ffb-review-case-of-sleepwalkers-niece.html)

ReplyDeleteI'm still collecting Perry Mason mysteries. I intend on reading them all in order as soon as I acquire the last couple I need.

ReplyDeleteBarry, George -- Sounds kinda like Lay's potato chips, "You can't eat just one." I "ate" these three last week. Probly need some meat and veggies for a while before I dip into the bag again.

ReplyDeleteGreat post, Mathew. I read most all the Perry Mason books when I was a teen but when I went back to try and reread a couple of years ago, I couldn't get into either of the books I'd picked up. (Can't remember what they were.) Sad to say, there are just some books better left in the past and Perry Mason is apparently it for me. I wish it were otherwise since I know I enjoyed them as a kid. But I disagree with you about Raymond Burr - I loved him as Mason. I loved the rest of the cast as well. I thought your descriptions of the literary Mason fit Raymond Burr pretty well. He had that impassive face thing going on, with intelligence brimming in his eyes. Yeah. And in truth he didn't really get really stout until the series was well along and even then I didn't mind it at all. It suited him. There are Perry Mason movies too, the ones starring Warren William (swoon) are especially hard to find. They are very different from the books and the TV show. At least in memory. :)

ReplyDeleteThanks, Yvette. Your defense of Raymond Burr is of Perry Mason caliber! I had the later image in mind when I wrote this, but in the earlier photos I could see he fit the written descriptions better. I should have qualified this as an "impressionistic interpretation" to allow for that discrepancy. But I shall remain firm with the word "windbag." ;)

Delete