With a

title like Killers of the Flower Moon: the Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI,

all that's left to tell, when you think about it, are the details.

But, oh mercy, those details.

It's a

tragically true story peppered with fiction:

the

lies one race of people consistently told another race. And we

already know which was the lying race, considering we're looking once

again at our history of "forked tongue" in the conquering

and settling of the American West by a land-hungry nation of

Bible-toting fortune seekers. We already know plenty of blood was

spilled by both races in this struggle between appetite and survival.

This book rips away the fig leaf of public innocence that concealed

just how catastrophically evil the hungry ones became when they

deemed Oklahoma's Osage Indians nothing more than speed bumps in the

stampede to the feeding trough.

During a

sixteen-year period (1907-23) Osage County Indians were dying at

nearly twice the national rate, many of them suspiciously and some

obviously murdered. When state, local and private investigators

failed to solve any of the obvious murders, the infant FBI—then

known only as the Bureau of Investigation and directed by a shady

former private detective—took a look, and got nowhere. Then J.

Edgar Hoover became director. Hoover assigned Special Agent Tom

White, a former Texas Ranger with an exemplary reputation, to revisit

the failed investigations. The result led to the conviction of an

important white resident of the county and several henchmen.

More

recently, in 1992, Dennis

McAuliffe Jr., a

Washington

Post

editor and grandson of another Osage Indian whose death had been

suspicious, looked deeper and concluded that many more Indians than

initially thought most likely were murdered. McAuliffe’s

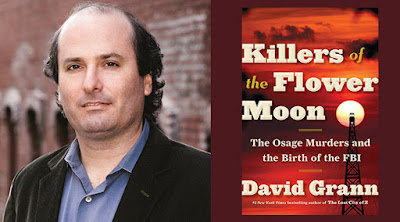

work was followed by David Grann, the New

Yorker

staff writer who researched and authored this book, Killers

of the Flower Moon. Grann

dug even deeper, and found how incomprehensibly horrible the “Reign

of Terror” in Osage County actually had been.

|

| Special Agent Tom White and Boss |

|

| Dennis McAuliffe |

Grann

quotes Garrick Bailey, a leading anthropologist on Osage culture, as

saying he believed “a high percentage of the county’s leading

citizens” were behind the killings. “Indeed,” Grann concludes,

“virtually every element of society was complicit.” One of the

victims was Barney McBride, a wealthy white oilman who was shot to

death in Washington where he’d gone carrying an appeal by the Indians

for a federal investigation. McBride, Grann says, “threatened to

bring down...a vast criminal operation that was reaping millions and

millions of dollars.”

Ah, finally, a clue to the motive besides

“the only good injun is a dead injun.”

Oil!

An

underground sea of the “black gold” lay under land the Osage

ended up owning after more than a century of U.S. treachery

(including that of Pres. Thomas Jefferson). The government might have

gotten hold of the oil as well as the nearly hundred million acres of

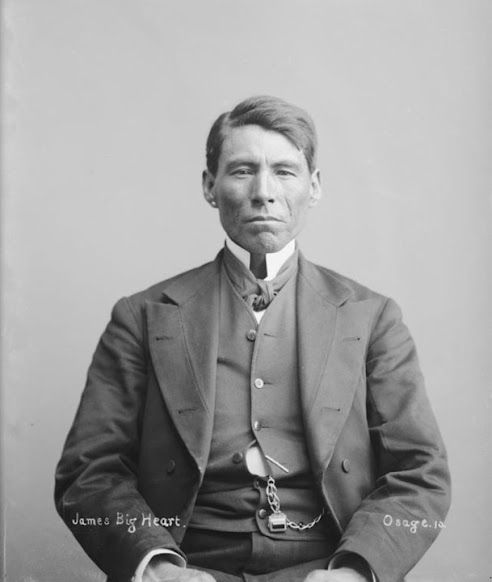

Osage ancestral land had it not been for tough Indian bargaining led

by Chief James Big Heart,

who spoke seven languages, including Sioux, French, English, and

Latin, and John Palmer, a lawyer whose mom was Osage. Buying their

reservation allotment the Osage managed to include in the transaction

that “the oil, gas, coal, or other minerals covered by the lands…

are hereby reserved to the Osage Tribe.” The Indians knew somehow,

Grann writes, their reservation rested upon oil deposits.

|

| Chief Big Heart |

According

to the allotment provisions, the Osage would own the mineral rights

even after selling their land. Each tribe member received what was

called a “headright,” which could not be sold, and was passed

down through the generations.

Well, lo

and behold, prospectors “discovered” the oil, and Indians owning

these headrights now were entitled to quarterly royalties from its

commercial sale. Suddenly the Osage were rich, and suddenly Osage

maidens were more attractive than ever to white men who wanted to

marry them. And marry them they did, and everyone might have lived

happily ever after, but…

There was a catch. Naturally.

Whoever first suggested that women always get the last word evidently

overlooked the U.S. Congress. Responding to popular concern about the

potential for irresponsible spending by the Osage of their new-found

wealth, the lawmakers decreed that “guardians” be appointed to

oversee this spending. The guardians, of course, were white.

One white

with good intentions, W. W. Vaughan, an attorney and former

prosecutor who vowed to eliminate the criminal element that was a

“parasite upon those who make their living by honest means,” was

murdered and thrown from the train he was taking home from Oklahoma

City after visiting the dying Chief Big Heart,

who’d been poisoned.

“The

justice of the peace was asked by a prosecutor if he thought that

Vaughan had known too much.” Grann says. “The justice replied,

‘Yes, sir, and had valuable papers on his person.’”

|

| W.W. Vaughan and family |

Are we

catching the drift here? Do we pick up a whiff of stink learning that

Indians with headrights or in line to inherit them begin dying

mysteriously, perhaps from poison, or from solidified lead propelled

by gunpowder? Or, as in one case, when their home explodes to

smithereens in the middle of the night while they’re in bed asleep?

Read Killers

of the Flower Moon

and the stench will gag you.

You might wonder, knowing this

overpowering circumstantial evidence, why the local justice system in

Osage County couldn’t come up with any solid evidence. Understandably, forensic science was barely existent then—even

after the fledgling FBI got involved—and witnesses might be reluctant to testify, not knowing who if anyone in

their community they could trust.

“The

murders had created a climate of terror that ate at the community,”

according to Grann. “People suspected neighbors, suspected friends.

“A

visitor...later recalled that people were overcome by

‘paralyzing fear,’ and a reporter observed that a ‘dark cloak

of mystery and dread…covered the oil-bespattered valleys of the

Osage hills.’”

Grann writes, “All efforts

to solve the mystery had faltered. Because of anonymous threats, the

justice of the peace was forced to stop convening inquests into the

latest murders. He was so terrified that merely to discuss the cases,

he would retreat into a back room and bolt the door. The new county

sheriff dropped even a pretense of investigating the crimes. ‘I

didn’t want to get mixed up in it,’ he later admitted, adding

cryptically, ‘There is an undercurrent like a spring at the head of

the hollow. Now there is no spring, it is gone dry, but it is broke

way down to the bottom.’

“Of

solving the cases, he said, ‘It is a big doings and the sheriff and

a few men couldn’t do it. It takes the government to do it.’”

“The

world’s richest people per capita were becoming the world’s most

murdered,” Grann sums up. “The press later described the killings

as being as ‘dark and sordid as any murder story of the century’

and the ‘bloodiest chapter in American crime history.’”

[For

more Friday's Forgotten Books check the links on Patti

Abbott's unforgettable blog]