Twenty-one

years

ago when Howard Fast was 82, he told an interviewer

he felt

compelled

his entire

life

to write. "If

I hadn't been able to become a good writer," he

told her,

"I'd have been a bad writer." As

I've read only one of the Fast's

85 published

books, I'm unqualified to determine in

sum which kind of writer he became. But if the average is even only

half as good as The

Case of the Poisoned Eclairs

I wouldn't be sticking my neck out too far to go with "good

writer." And I think it's safe to add that considering perhaps

his best-known work, Spartacus,

and his best-selling "Immigrants" series, we can bump that

average up to damned good writer. I've a hunch his fingers were still

trying to type more words when the final deadline caught up with him

at age 88.

I finally

caught up with Fast last week. The only excuse I can come up with is

that I'd always thought his name was a pseudonym for a "real"

author who didn't want his/her name associated with the potboilers

he/she was churning out. No evidence, just a feeling that a name like

"Howard Fast" was...oh, too paperback oriented, maybe? As

it turned out I came to Fast through the back door, thinking one of

his pseudonyms, E. V. Cunningham, was the real name for "Howard

Fast." I know. It's

a mixed up, muddled up, shook up world, but what the hey. And even

then I might not have read The

Case of the Poisoned Eclairs

but for my mystery blogger friend Tracy,

who lured me in with her review of one of Cunningham/Fast's seven

Masao Masuto mysteries. Ah so. Permit me to note that Tracy's love of

mysteries includes the mystery of her last name, a mystery I have yet

to solve.

The

Case of the Poisoned Eclairs is

the fourth in the series, and I will be reading the others. What

attracted me in Tracy's review was the idea of a Nisei (American born

of Japanese parents) police detective in Beverly Hills. Masao Masuto

and his Nisei wife do say "ah so" from time to time, but I

get the sense they use that stereotypical Asian expression for a

little ironic fun. The characters in this 1979 novel still refer to

Asians as "Orientals," and aren't hip yet to calling them

"Asians." Masuto is good natured about the ribbing he

takes, and only gently enlightens people who mistake him for Chinese.

He even gently explains to his boss, Capt. Wainwright, that his

(Masuto's) eyes are not slanted:

“'I

have always defended you as a non-racist,' Masuto said unhappily. 'My

eyes don’t actually slant, so it’s a kind of unhappy euphemism—'”

Wainright apologizes, claiming

he "got excited."

Masuto even pokes fun at

himself. He and his partner Sy Beckman, who between them comprise the

entire Beverly Hills homicide division, rib each other, as most cops

do, but in this case the rib bone is Masuto's Japanese anestry, and

he frequently starts it. Here's an example:

“What is it, Sy? What did

you learn?”

“You give me a creepy

feeling at times.”

“That’s because

I’m a wily Oriental."

As I read

along I started wondering if maybe Howard Fast was Asian, and if not,

wasn't he treading a tad on thin ice making fun of his character's

heritage, albeit some years before "political correctness"

raised its ubiquitous censorious head? Two things I’ve learned.

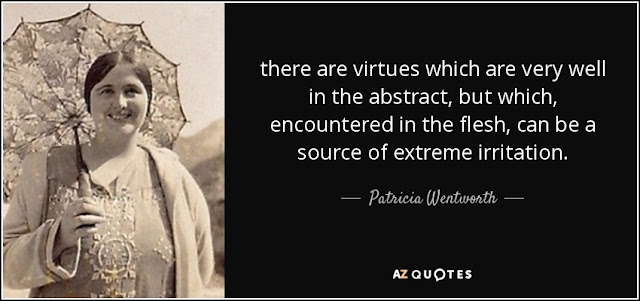

Fast was a Jewish Communist, and, having spent some time in prison

for refusing to give names to the House Un-American Activities

Committee, presumably knew rather well the risks he was taking with

ethnic sensitivities. Also, as the author of The

Art of Zen Meditation,

and

presumably a practicing Zen Buddhist himself, Fast undoubtedly knew

rather well the thoughts and actions of his Zen Buddhist chief

character.

|

| Howard Fast |

The

spirit of ommmmmmmmm...

certainly resonated off the page with me. I found Sgt. Masao Masuto’s

Zen-disciplined manner, including his police voice, a pleasant,

sinus-calming contrast with the usual wise-cracking, angst-ridden

cops and detectives in all of the other crime novels I’ve read that

immediately come to mind. Here he is doing a little introspection

after the pretty, blonde secretary at his headquarters flirts with

him:

“He

never thought of himself as likable or lovable, a tall, dour-faced

second generation Japanese man, yet nothing pleased him more than

this almost consistent response on the part of women. He pardoned

himself;

he argued to himself that he had a good wife whom he loved, that he

was scrupulous in his behavior as a policeman, that he was content.

Or was he?”

A

little mystery never hurt anyone.

But

the damned eclairs did. First they killed a maid who took some home

when the ladies for whom the eclairs were intended—all of them

professing diet restrictions--turned them down. Then a dog dies when

it eats a piece of candy. The dog belonged to one of the dieting

ladies.

Masuto

and Beckman soon learn both corpses died of botulism poisoning.

Because of the poison’s nature which needs an airtight container in

which to grow, the detectives conclude someone had injected botulism

toxin into the pastries and candy. The women are wealthy divorcees,

and their ex-husbands the likely suspects.

Not

the most original of plot types, but the police work is authentic in

this essentially procedural mystery. I would have enjoyed the solving

of the case with any of the detectives I’ve read and enjoyed. But

there was something special about Masuto and Beckman working it. I

could say this special something was inscrutable, but I don’t have

the experience to make such ethnic fun. Wouldn’t be prudent, and,

anyway, wouldn’t be funny.

Besides,

I know what it was. The calm, good-humored voice, the effortless

narrative pacing, the Beverly Hills milieu, memorable supporting

Hollywood-type characters—one of the suspects is unquestionably

based on comedian Don Rickles-- and, yes, some first-rate suspense.

Ah

so.

|

| Fast refusing to give names to HUAC |

[For

more Friday's Forgotten Books check the links on Patti

Abbott's unforgettable blog]