The

word serendipity

was

born in

1754 when

Horace

Walpole made

it up for a

fairytale he

was writing.

Today,

the New Oxford American Dictionary defines

serendipity

as

“the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or

beneficial way.” This I learned happily

reading

David Markson’s The

Last Novel.

I had not

known of Markson or his work until several weeks ago perusing a

blogpost’s comment thread. I don’t recall whose blog, or whose

rave endorsements of Markson prompted me to look him up on

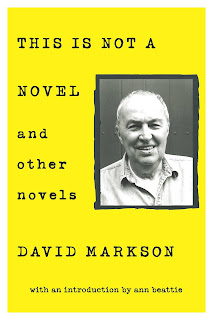

Amazon.com, where I downloaded the Kindle version of This

is Not a Novel, and Other Novels,

which is actually one long list of quotations, odd facts, and

personal observations, broken into three parts, with the third part

titled The

Last Novel.

I

learned also that fish feel no pain, and that Thomas Hardy’s first

wife, Emma, kept a twenty-year diary devoted to assassinating his

character, and that upon her death he burned the infuriating

thing.

I learned so so so much more

in The Last Novel, which I almost abandoned after the first

few pages, for which I am chagrined and embarrassed to the extent I

feel an overwhelming pressure to confess—right here right now, in

this very space. Some might find it mitigating that I had no idea

what I was getting into when I downloaded This is Not a Novel, and

Other Novels, thinking it

possibly a sort of post-post modern crime novel because the blogpost

discussion launching

the

adventure, which caused me to buy also a David Goodis crime novel,

had mentioned that David Foster Wallace was a Markson admirer. (I

have resolutely refused even to consider reading anything by David

Foster Wallace on grounds he was a darling of the incestuous

New York literati, yet his endorsement of Markson did attach a

certain twisted cachet in the same vein as Einstein’s having kept a

few Perry Mason paperbacks hidden in his Princeton University

office.)

I

suppose it is possible the Wallace connection, in

addition to fancying something

different, prompted me to open Markson’s book before Goodis’s. I

started with Ann Beattie’s fawning introduction. They were friends,

she discloses, and her lengthy literary tribute is “over the moon,”

to borrow her phrase. But she pulled me in with this line:

“Try to stop reading

one of these three novels. Meanings accrue;

mysteries arise;

you laugh when you least expect to laugh.”

I took it as the challenge it

was meant to be, read a couple of pages of each novel, resisting all

the way because they weren’t what I’d expected, and clicked the

book back into the library. I even opened the Goodis novel,

Nightfall, knowing it would be good, but I delayed starting

it, bothered by my disappointment with the Markson. Finally opened

Markson again and re-read Ann Beattie’s intro. Then I skipped to

The Last Novel and

started reading again, and before I could again say “What the hell

is this thing?” found myself over the moon and on my way to Mars.

Beattie was right. I could not stop.

Novel: Wondering when

and where the last casual streetcorner conversation in Latin might

have taken place.

[I laughed.]

Novel: Dante will

always remain popular because nobody ever reads him. Said Voltaire.

[Ditto]

Novel:

It

Ain’t Necessarily So.

In Danish. Which was piped into Danish radio by the underground

whenever announcements were made of German victories in World War II.

[Catching

the drift?]

Novel:

Pietro Aretino died in the midst of a hysterical fit of laughter that

apparently turned into an apoplectic stroke. As had the Athenian

comic playwright Philemon — at ninety-nine. Or one hundred and one.

[Not only did I have trouble

taking a break from reading The Last Novel, I’m having

trouble restraining myself from copying all of its lines to this

report!]

Okay,

one more: Yasser Arafat was reported not to have

read one book in the last forty years of his life. But to have spent

innumerable hours enrapt by Tom and Jerry cartoons.

Somewhere along my rush

through Markson’s astonishing collection of anecdotes, quotes,

observations and personal opinions, the serendipitous element I

mentioned above was taking shape just beneath the surface of my

consciousness: Tangney.

|

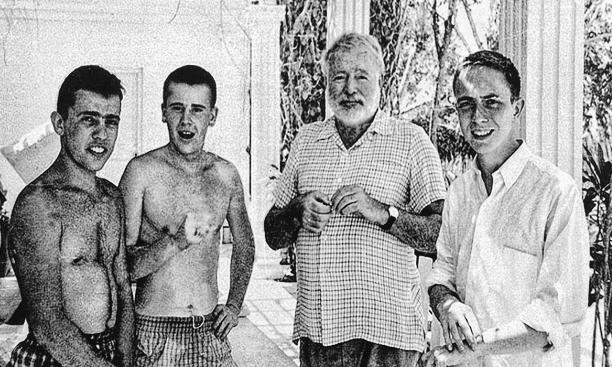

| Tangney (second from left) |

William E. Tangney,

interviewer

of Hemingway, discoverer of Einstein’s Perry Mason

books, founding editor of the York Town Crier (later changed to its

more corporate-comfortable name Yorktown

Crier), assembler of anecdotes, quotes, odd facts, and

personal observations. Missing friend. I lost touch with Tangney

nearly two decades ago after he left Virginia for Naples, Florida. He

refuses to communicate online, rarely answers his phone, and never

answers letters. Yet, a welcoming and genial host. I visited him

regularly when he lived in a book-crammed Yorktown house owned by

Mary Mathews, the Greek restaurateur he’d persuaded to pony up the

cash to birth a weekly newspaper that’s now owned by a regional

chain. Bill is a spellbinding storyteller, a constant reader and

compulsive taker of notes. His grand strategy was eventually to

publish his assemblage of quotes and quips and curious minutia in a

book. I don’t know if this has come to pass. Two days ago I got his

address from WhitePages.com and had Amazon.com send him a copy of

This is Not a Novel, and Other Novels. It should arrive today.

Bill may be piqued by such cheek, but he’ll have some laughs.

Novel: Anthony Trollope

was once told by an acquaintance that one of his recurring serialized

characters had become boring. Trollope killed her off in the next

installment.

[Hahahahaha]

Novel: If it were up to

me, I would have wiped my behind with his last decree. Said Mozart —

after a demand by the Archbishop of Salzburg for more brevity in his

church compositions.

Baldur von Schirach, one of

the chief Nazi war criminals tried at Nuremberg, on the origin of his

anti-Semitism: From a book about the Jews by Henry Ford.

If on a winter’s night with

no other source of warmth, Novelist were to burn an Andy Warhol,

qualms? Qualmless.

Pushkin’s beautiful

seventeen-year-old wife Nathalie, whom he married at thirty-one —

and whom he said was the one hundred and thirteenth woman he had been

in love with.

1922.

Ulysses.

1922. The

Waste Land.

1922. Reader’s Digest.

There are four chances in

2,598,960 of being dealt a royal flush in a hand of poker.

How old would you be if you

didn’t know how old you was? -- Satchel Paige.

Please return this book. I

find that though many of my friends are poor mathematicians, they are

nearly all good bookkeepers. -- Walter Scott’s bookplate.

No battleship has yet been

sunk by bombs. Said the caption on a photograph of the USS Arizona in

the program for the 1941 Army-Navy football game — eight days

before Pearl Harbor.

Never having realized that

there originally once was an actual troublemaking Irish family named

Hooligan.

Or a military officer named

Shrapnel.

The John Cage composition

entitled 4’33”, in which the performer sits at a piano for four

minutes and thirty-three seconds — and plays nothing.

Wondering if there can be any

other ranking twentieth-century American poet whose body of work

contains even half the percentage of pure drivel as Wallace Stevens’.

A sort of gutless Kipling,

Orwell called Auden.

I’m going. I find the

company very uncongenital. Says someone in a Gypsy Rose Lee mystery.

The French government provides

the Paris Opera a subsidy of roughly $ 135,000,000 each year. The

United States gives the Metropolitan Opera less than $ 1,000,000.

[potato chips for the curious,

good-humored mind]

Abject bottom-licking

narcissism — Martha Gellhorn found in Hemingway.

Morningless sleep, Epicurus

called death.

One would like to curse them

so that thunder and lightning strike them, hell-fire burn them, the

plague, syphilis, epilepsy, scurvy, leprosy, carbuncles, and all

diseases attack them. Ignorant asses. -- Martin Luther, in a

contemplative mood re the papal hierarchy.

A writer of something

occasionally like English — and a man of something occasionally

like genius, Swinburne called Whitman. A man standing up to his neck

in a cesspool — and adding to its contents, Carlyle called

Swinburne.

It is utterly impossible to

persuade an editor that he is nobody. Said William Hazlitt.

Comedy aims at representing

men as worse, tragedy as better, than in actual life. Says Aristotle.

Berlioz read every Fenimore

Cooper novel as quickly as it appeared. And admitted that fully four

hours after he finished The Prairie he was still weeping over the

death of Natty Bumppo.

A dreadful old fraud, Edmund

Wilson called Robert Frost. A sententious, holding-forth old bore who

expected every hero-worshipping adenoidal little twerp of a

student-poet to hang on his every word, James Dickey would elaborate

subsequently.

The eighteenth-century

evangelist George Whitefield. Whose pulpit voice was so effective,

said David Garrick, that he could make listeners laugh or cry by no

more than pronouncing the word Mesopotamia.

Dear President George W. Bush:

Herewith please find uncorrected proofs for the newly discovered

rewritten version of Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit. Kindly limit

your review to twelve thousand words. Thank you.

Remembering that Charles

Darwin is buried in Westminster Abbey.

For no reason whatsoever,

Novelist has just flung his cat out one of his

four-flights-up front windows.

[several pages later:

Novelist does not own a cat,

and thus most certainly could not have thrown one out a window.

Nonetheless he would lay odds that more than one hopscotching

reviewer will be reading carelessly enough here to never notice these

two sentences and announce that he did so.

I

am no Einstein, once said Einstein.

Listen,

I bought your latest book. But I quit after about six pages. That’s

all there is, those little things?

[And

I still have the first two lists of “those little things” to

read!]

No comments:

Post a Comment